GILLINGHAM (WOODLANDS) CEMETERY

Kent

England

Visiting Information

A Visitor Information Panel has recently been installed at Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery to provide information about the war casualties buried here. This is one of many panels being erected to help raise awareness of First and Second World War graves in the UK (Aug 2013).

Historical Information

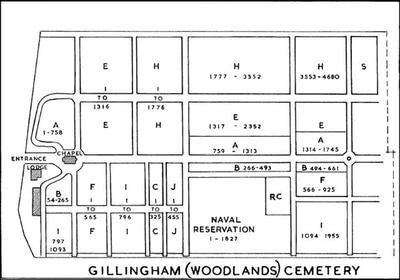

There is a large naval section in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery which was reserved by the Admiralty and served the Royal Naval Hospital in Windmill Road. The section contains most of the war graves as well as burials of the pre-war and inter-war years.

Among the First World War burials in the naval section are those from HMS 'Bulwark', blown up in Sheerness Harbour in November 1914, HMS 'Princess Irene' which suffered an internal explosion in May 1915 and HMS 'Glatton' which suffered the same fate in Dover Harbour in September 1918 (the bodies were not recovered until March 1930). The plot also contains a number of graves resulting from the air raid on Chatham Naval Barracks on 3 September 1917.

In all, Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery contains 837 burials and commemorations of the First World War. 82 of the burials are unidentified and there are special memorials commemorating a number of casualties buried in other cemeteries in the area whose graves could not be maintained.

Second World War burials number 385, 21 of these burials are unidentified. Most are in the naval section.

There are 2 Foreign National war burials and 2 non war service burials.

Cemetery pictures used with the permission of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

A Visitor Information Panel has recently been installed at Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery to provide information about the war casualties buried here. This is one of many panels being erected to help raise awareness of First and Second World War graves in the UK (Aug 2013).

Historical Information

There is a large naval section in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery which was reserved by the Admiralty and served the Royal Naval Hospital in Windmill Road. The section contains most of the war graves as well as burials of the pre-war and inter-war years.

Among the First World War burials in the naval section are those from HMS 'Bulwark', blown up in Sheerness Harbour in November 1914, HMS 'Princess Irene' which suffered an internal explosion in May 1915 and HMS 'Glatton' which suffered the same fate in Dover Harbour in September 1918 (the bodies were not recovered until March 1930). The plot also contains a number of graves resulting from the air raid on Chatham Naval Barracks on 3 September 1917.

In all, Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery contains 837 burials and commemorations of the First World War. 82 of the burials are unidentified and there are special memorials commemorating a number of casualties buried in other cemeteries in the area whose graves could not be maintained.

Second World War burials number 385, 21 of these burials are unidentified. Most are in the naval section.

There are 2 Foreign National war burials and 2 non war service burials.

Cemetery pictures used with the permission of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Lieutenant-Commander Eugene Kingsmill Esmonde, V. C., D. S. O.

H. M. S. Daedalus (825 Squadron) Royal Navy, died 12th February 1942, aged 32. Plot Royal Naval Reservation. Grave 187. R. C.

Son of John Joseph and Eily Esmonde, of Drominagh, Co. Tipperary, Irish Republic.

Citation: The following details are given in the London Gazette of 3rd March, 1942 : The King has been graciously pleased to approve the grant of the Victoria Cross, for valour and resolution in action against the enemy, to Lieut.-Comdr. Eugene Esmonde, D.S.O., R.N. On 12th February, 1942, Lieut.-Comdr. Esmonde was in command of a squadron of six Swordfish ordered to attack the German battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Prinz Eugene, which were entering the Straits of Dover strongly escorted by some thirty surface craft. After ten minutes'' flight his squadron was attacked by a strong force of enemy fighters. Touch was lost with his fighter escort and all his aircraft were damaged. Nevertheless, cool and resolute, challenging hopeless odds, he flew on towards the target through the deadly fire of the battle-cruisers and their escorts. The port wing of his aircraft was shattered, but still he led his squadron on, only to be quickly shot down. His high courage and splendid resolution will live in the traditions of the Royal Navy and remain for many generations a fine and stirring memory

H. M. S. Daedalus (825 Squadron) Royal Navy, died 12th February 1942, aged 32. Plot Royal Naval Reservation. Grave 187. R. C.

Son of John Joseph and Eily Esmonde, of Drominagh, Co. Tipperary, Irish Republic.

Citation: The following details are given in the London Gazette of 3rd March, 1942 : The King has been graciously pleased to approve the grant of the Victoria Cross, for valour and resolution in action against the enemy, to Lieut.-Comdr. Eugene Esmonde, D.S.O., R.N. On 12th February, 1942, Lieut.-Comdr. Esmonde was in command of a squadron of six Swordfish ordered to attack the German battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Prinz Eugene, which were entering the Straits of Dover strongly escorted by some thirty surface craft. After ten minutes'' flight his squadron was attacked by a strong force of enemy fighters. Touch was lost with his fighter escort and all his aircraft were damaged. Nevertheless, cool and resolute, challenging hopeless odds, he flew on towards the target through the deadly fire of the battle-cruisers and their escorts. The port wing of his aircraft was shattered, but still he led his squadron on, only to be quickly shot down. His high courage and splendid resolution will live in the traditions of the Royal Navy and remain for many generations a fine and stirring memory

SS/4751 Able Seaman

Alfred Taylor

H.M.S. Vindictive, Royal Navy

24th April 1918, aged 23.

Son of Charles and Elizabeth Taylor, of Woodbine Cottage, Finstown, Firth, Orkney.

Naval. 8. 414.

Portrait courtesy of Brian Budge.

Grave picture courtesy of Jon Saunders.

Alfred Taylor

H.M.S. Vindictive, Royal Navy

24th April 1918, aged 23.

Son of Charles and Elizabeth Taylor, of Woodbine Cottage, Finstown, Firth, Orkney.

Naval. 8. 414.

Portrait courtesy of Brian Budge.

Grave picture courtesy of Jon Saunders.

Two Orcadian Brothers

(By Brian Budge)

Two Orcadian Taylor brothers died after fighting in two of the epic actions of the Great War. John Charles Taylor was born at Rusland, Harray on 28th May 1884, the first son, after two older daughters, of Charles Taylor and Elizabeth Taylor (née Brown). Another son and daughter followed,before Alfred Taylor was born at Millgoe, Firth on 21st May 1894.

Charles Taylor was a farm servant, working at Binscarth, Finstown when the 1901 census was taken. John was then working as a ploughman at Moan, Harray. John emigrated to Canada, probably before his mother died at Millgoe of appendicitis on 1st May 1910. John Taylor was working as a locomotive engineer when the Great War started. He enlisted into the 21st Alberta Hussars on 22nd August 1914, at Medicine Hat. John travelled east to join the First Contingent at Valcartier Camp, Quebec and then attested into the 10th Battalion, C.E.F. on 24th September. Five days later John embarked on the SS Scandinavian in Quebec City docks, sailed with the fleet carrying and escorting the First Contingent on 3rd October.

10th Battalion, C.E.F. landed at Plymouth on 14th October and moved to Salisbury Plain to spend four months training there. 10th Battalion was then packed into an old cattle boat, the Kingstonian, and sailed to St. Nazaire in France. The boat ran aground there in a gale, but 10th Battalion finally disembarked on 15th February 1915. 10th Battalion manned front line trenches during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle a month later, but did not attack. It then moved north into Flanders, when the Canadian Division moved into the line north of Ypres.

When the Germans launched the first gas attack north of Ypres at 5 pm on 22nd April, 10th Battalion was in divisional reserve in Ypres. The release of chlorine gas had forced back the French troops on the left of the Canadians’ front, leaving a gap about 4½ miles wide. 10th Battalion moved up that evening to 3rd Brigade H.Q. at Mousetrap Farm, where it was ordered to attack that night with 16th Battalion into the gap.

Just before midnight the two Canadian battalions advanced towards an oak plantation, known afterwards as Kitchener’s Wood. The Germans heard their advance, so lit it with flares and poured rifle and machine gun fire onto the Canadians. They pushed on into the wood and, in fierce hand-to-hand fighting in the dark, killed or drove out the Germans holding it. Heavy German artillery fire reduced the strength of the force in the wood to less than 500 men, who withdrew at 5 am on the 23rd to a line along its southern edge, prolonged by 3rd Battalion to St. Julien. During the day British, French and Canadian reserves deployed to fill the gap on the Canadians’ left, while all took heavy casualties from unremitting German fire.

At 4 am on the 24th the Germans launched a gas attack against the Canadian front, most of which held despite having only improvised protection. However, the Germans penetrated the front of 15th Battalion and the Canadians and reserve British troops fought a desperate and costly battle to seal the breach. 10th Battalion took many more casualties during three days of fighting to hold the position known as Location “C” on Gravenstafel Ridge.

10th Battalion pulled back from the front on 27th April, but moved two days later into reserve trenches guarding Nos. 3 and 4 Bridges over the Yser Canal. Intermittent German shelling caused more casualties, including John Taylor, who was killed in action on 3rd May, aged 30. 10th Battalion lost 485 casualties in the Second Battle of Ypres. John was one of many whose body was not identified; they are commemorated on Panel 24 of the Menin Gate in Ieper.

Alfred Taylor also left Orkney before the Great War, enrolling into the Royal Navy as an Ordinary Seaman at Chatham on 10th February 1914. Alfred had almost completed his basic training there, when war broke out. He joined the 25,000 ton new battleship, HMS Benbow, on 7th October and then sailed with it to join the Grand Fleet three days later in its main base, Scapa Flow in Orkney.

Alfred Taylor was promoted Able Seaman on 10th February 1916. HMS Benbow remained with the Grand Fleet throughout the Great War; it took part in the Battle of Jutland and was not damaged. Alfred was luckier than most of the battleship’s crew, because visiting his family in Finstown did not require long boat and train leave journeys, also he probably had extra opportunities to see them.

After Jutland the German High Seas Fleet did make several sorties to try and attack the Grand Fleet. However, most of the Grand Fleet sailors spent many boring months lying at anchor in Scapa Flow. Alfred was a volunteer in early February 1918 to a call for officers and other ranks to take part in “a secret and dangerous mission”. The Grand Fleet easily found 200 volunteer sailors to join 740 Royal Marines of the 4th Battalion for that mission. On 1st March Alfred arrived back at Chatham, where the force for a raid to block Zeebrugge and Ostend Harbours was concentrating.

The sailors boarded on an old battleship, HMS Hindustan, while they spent a month training in close quarter fighting. That included using the bayonet, Mills bombs, Lewis light machine guns and Stokes mortars, also exercises, some at night, against locally based Territorial soldiers. Alfred was one of the 100 sailors assigned to the 5600 ton old cruiser, HMS Vindictive, the others boarded two Mersey ferries, Daffodil and Iris, and Royal Marines joined all three ships. They were to come alongside the mole at Zeebrugge and land storming parties, to distract the German defences while blockships sailed into the harbour and blocked the canal to Bruges.

After a cancellation on 12th April while the ships were approaching the Belgian coast, they pressed on towards Zeebrugge harbour on the night of the 22nd. Vindictive was 300 yards out when the wind blew away her smoke screen. Alert German gunners poured fire onto the ship and cut down almost half of the landing parties, sheltered behind improvised deck protection.

A battered Vindictive came alongside the Zeebrugge mole at 0001 hrs on the 23rd, St. George’s Day. Daffodil pushed to hold her there for fifty minutes, while sailors and marines struggled ashore under heavy fire. Only about 200 made it onto the mole and none even reached the German gun batteries. However, the three blockships did sail into the harbour, covered by a smokescreen most of the way. Thetis was sunk before she could ram the lock gate, but Intrepid and Iphignia pressed on to ground in the Bruges channel and exploded charges to scuttle there.

Iris, Daffodil and Vindictive had by then sailed from the mole, having retrieved most of the surviving landing force, except a platoon that failed to recognise the withdrawal signal. The Ostend raid failed altogether, while the Zeebrugge raid only blocked the channel for a few days. However, they provided a major boost to British civilian morale, at a time when the B.E.F. was fighting desperately to stop the Germans reaching the Channel ports, and for its own survival.

British casualties at Zeebrugge were 161 killed, 411 wounded, 16 missing and 13 taken prisoner, from a total force of about 1,300. Alfred Taylor died of wounds, aged 23, on 24th April, one of 28 who did soon after the raid. He is buried, with many other raid casualties, in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery. He is commemorated, with his brother John, on the Firth Memorial. One of their sisters unveiled the memorial, during its dedication on Sunday, 26th December 1921.

Charles Taylor was a farm servant, working at Binscarth, Finstown when the 1901 census was taken. John was then working as a ploughman at Moan, Harray. John emigrated to Canada, probably before his mother died at Millgoe of appendicitis on 1st May 1910. John Taylor was working as a locomotive engineer when the Great War started. He enlisted into the 21st Alberta Hussars on 22nd August 1914, at Medicine Hat. John travelled east to join the First Contingent at Valcartier Camp, Quebec and then attested into the 10th Battalion, C.E.F. on 24th September. Five days later John embarked on the SS Scandinavian in Quebec City docks, sailed with the fleet carrying and escorting the First Contingent on 3rd October.

10th Battalion, C.E.F. landed at Plymouth on 14th October and moved to Salisbury Plain to spend four months training there. 10th Battalion was then packed into an old cattle boat, the Kingstonian, and sailed to St. Nazaire in France. The boat ran aground there in a gale, but 10th Battalion finally disembarked on 15th February 1915. 10th Battalion manned front line trenches during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle a month later, but did not attack. It then moved north into Flanders, when the Canadian Division moved into the line north of Ypres.

When the Germans launched the first gas attack north of Ypres at 5 pm on 22nd April, 10th Battalion was in divisional reserve in Ypres. The release of chlorine gas had forced back the French troops on the left of the Canadians’ front, leaving a gap about 4½ miles wide. 10th Battalion moved up that evening to 3rd Brigade H.Q. at Mousetrap Farm, where it was ordered to attack that night with 16th Battalion into the gap.

Just before midnight the two Canadian battalions advanced towards an oak plantation, known afterwards as Kitchener’s Wood. The Germans heard their advance, so lit it with flares and poured rifle and machine gun fire onto the Canadians. They pushed on into the wood and, in fierce hand-to-hand fighting in the dark, killed or drove out the Germans holding it. Heavy German artillery fire reduced the strength of the force in the wood to less than 500 men, who withdrew at 5 am on the 23rd to a line along its southern edge, prolonged by 3rd Battalion to St. Julien. During the day British, French and Canadian reserves deployed to fill the gap on the Canadians’ left, while all took heavy casualties from unremitting German fire.

At 4 am on the 24th the Germans launched a gas attack against the Canadian front, most of which held despite having only improvised protection. However, the Germans penetrated the front of 15th Battalion and the Canadians and reserve British troops fought a desperate and costly battle to seal the breach. 10th Battalion took many more casualties during three days of fighting to hold the position known as Location “C” on Gravenstafel Ridge.

10th Battalion pulled back from the front on 27th April, but moved two days later into reserve trenches guarding Nos. 3 and 4 Bridges over the Yser Canal. Intermittent German shelling caused more casualties, including John Taylor, who was killed in action on 3rd May, aged 30. 10th Battalion lost 485 casualties in the Second Battle of Ypres. John was one of many whose body was not identified; they are commemorated on Panel 24 of the Menin Gate in Ieper.

Alfred Taylor also left Orkney before the Great War, enrolling into the Royal Navy as an Ordinary Seaman at Chatham on 10th February 1914. Alfred had almost completed his basic training there, when war broke out. He joined the 25,000 ton new battleship, HMS Benbow, on 7th October and then sailed with it to join the Grand Fleet three days later in its main base, Scapa Flow in Orkney.

Alfred Taylor was promoted Able Seaman on 10th February 1916. HMS Benbow remained with the Grand Fleet throughout the Great War; it took part in the Battle of Jutland and was not damaged. Alfred was luckier than most of the battleship’s crew, because visiting his family in Finstown did not require long boat and train leave journeys, also he probably had extra opportunities to see them.

After Jutland the German High Seas Fleet did make several sorties to try and attack the Grand Fleet. However, most of the Grand Fleet sailors spent many boring months lying at anchor in Scapa Flow. Alfred was a volunteer in early February 1918 to a call for officers and other ranks to take part in “a secret and dangerous mission”. The Grand Fleet easily found 200 volunteer sailors to join 740 Royal Marines of the 4th Battalion for that mission. On 1st March Alfred arrived back at Chatham, where the force for a raid to block Zeebrugge and Ostend Harbours was concentrating.

The sailors boarded on an old battleship, HMS Hindustan, while they spent a month training in close quarter fighting. That included using the bayonet, Mills bombs, Lewis light machine guns and Stokes mortars, also exercises, some at night, against locally based Territorial soldiers. Alfred was one of the 100 sailors assigned to the 5600 ton old cruiser, HMS Vindictive, the others boarded two Mersey ferries, Daffodil and Iris, and Royal Marines joined all three ships. They were to come alongside the mole at Zeebrugge and land storming parties, to distract the German defences while blockships sailed into the harbour and blocked the canal to Bruges.

After a cancellation on 12th April while the ships were approaching the Belgian coast, they pressed on towards Zeebrugge harbour on the night of the 22nd. Vindictive was 300 yards out when the wind blew away her smoke screen. Alert German gunners poured fire onto the ship and cut down almost half of the landing parties, sheltered behind improvised deck protection.

A battered Vindictive came alongside the Zeebrugge mole at 0001 hrs on the 23rd, St. George’s Day. Daffodil pushed to hold her there for fifty minutes, while sailors and marines struggled ashore under heavy fire. Only about 200 made it onto the mole and none even reached the German gun batteries. However, the three blockships did sail into the harbour, covered by a smokescreen most of the way. Thetis was sunk before she could ram the lock gate, but Intrepid and Iphignia pressed on to ground in the Bruges channel and exploded charges to scuttle there.

Iris, Daffodil and Vindictive had by then sailed from the mole, having retrieved most of the surviving landing force, except a platoon that failed to recognise the withdrawal signal. The Ostend raid failed altogether, while the Zeebrugge raid only blocked the channel for a few days. However, they provided a major boost to British civilian morale, at a time when the B.E.F. was fighting desperately to stop the Germans reaching the Channel ports, and for its own survival.

British casualties at Zeebrugge were 161 killed, 411 wounded, 16 missing and 13 taken prisoner, from a total force of about 1,300. Alfred Taylor died of wounds, aged 23, on 24th April, one of 28 who did soon after the raid. He is buried, with many other raid casualties, in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery. He is commemorated, with his brother John, on the Firth Memorial. One of their sisters unveiled the memorial, during its dedication on Sunday, 26th December 1921.

20824 Private

John Charles Taylor Canadian Infantry

3rd May 1915, aged 30.

Panel 24.

Son of Charles and Elizabeth Taylor, of Woodbine Cottage, Finstown, Orkney, Scotland.

Commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial

John Charles Taylor Canadian Infantry

3rd May 1915, aged 30.

Panel 24.

Son of Charles and Elizabeth Taylor, of Woodbine Cottage, Finstown, Orkney, Scotland.

Commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial