The Spirit Lives On

Text and pictures provided by Ken Wright

3rd September 1939. At 11-15 am, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain made this historic speech to the nation;

‘I am speaking to you from the cabinet room at 10 Downing Street. This morning, the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government an official note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock, that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received and consequently this country is at war with Germany.’

The British destroyer, H.M.S Kelly was at sea undergoing her shake down trials when her Captain, Lord Louis Mountbatten was handed an urgent message. It read; ‘From Admiralty. To all concerned at home and abroad. Most immediate. Commence hostilities at once with Germany.’ The brand new destroyer was now officially at war.

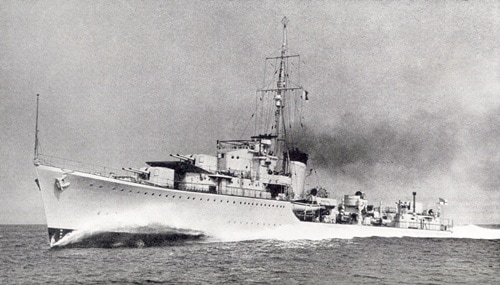

2nd April 1937. Kelly began her life as job lot number 615 at the R&W Hawthorn/Leslie & Company Limited shipyard at Hebburn-on-Tyne, Newcastle. She and her sister ship 614 [later named Jervis] were to be built to a radical and innovative new design by the Naval Architect, A.P. Cole. A frequent visitor to the shipyard, Lord Louis Mountbatten, contributed ideas to the design based on his many years' experience at sea. The two destroyers were to be Flotilla leaders and help fill the gap in the British destroyer strength. The men at the Hebburn ship yard worked hard to ensure these two ships would be their finest effort.

25th October 1938. Job lot 615 was christened H.M.S Kelly after the Admiral of the Fleet, John Kelly and in the spring of 1939, Lord Mountbatten became her Captain and took command of 5 Destroyer Flotilla [K class] made up of the destroyers; Kelvin, Kashmir, Khartoum, Kingston, Kipling, Kimberley and Kandahar.

‘I am speaking to you from the cabinet room at 10 Downing Street. This morning, the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government an official note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock, that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received and consequently this country is at war with Germany.’

The British destroyer, H.M.S Kelly was at sea undergoing her shake down trials when her Captain, Lord Louis Mountbatten was handed an urgent message. It read; ‘From Admiralty. To all concerned at home and abroad. Most immediate. Commence hostilities at once with Germany.’ The brand new destroyer was now officially at war.

2nd April 1937. Kelly began her life as job lot number 615 at the R&W Hawthorn/Leslie & Company Limited shipyard at Hebburn-on-Tyne, Newcastle. She and her sister ship 614 [later named Jervis] were to be built to a radical and innovative new design by the Naval Architect, A.P. Cole. A frequent visitor to the shipyard, Lord Louis Mountbatten, contributed ideas to the design based on his many years' experience at sea. The two destroyers were to be Flotilla leaders and help fill the gap in the British destroyer strength. The men at the Hebburn ship yard worked hard to ensure these two ships would be their finest effort.

25th October 1938. Job lot 615 was christened H.M.S Kelly after the Admiral of the Fleet, John Kelly and in the spring of 1939, Lord Mountbatten became her Captain and took command of 5 Destroyer Flotilla [K class] made up of the destroyers; Kelvin, Kashmir, Khartoum, Kingston, Kipling, Kimberley and Kandahar.

4th September 1939. The day after war was declared, Kelly with another destroyer, Acheron and an anti-submarine vessel left from Portland harbour on an early morning training exercise. They hadn’t been at sea long when suddenly the anti submarine boat frantically signalled Kelly; ‘torpedo approaching you.’ Kelly took immediate evasive action and the torpedo missed. All three ships began a search of the area. Their war had begun to get serious. Kelly got an asdic/sonar ‘ping’ and steamed over the position indicated and dropped a pattern of depth charges followed by Acheron which also launched a pattern of depth charges. Both destroyers covered the area again while the crews searched hopefully for any signs of wreckage. Several large patterns of oil were spotted which may have indicated a ‘probable’ kill or nothing at all.

17th September 1939. This was an evening Kapitanleutnant Otto Schuhart and the crew of U-Boat 29 would never forget. They had just scored the first major U-Boat success of the war by sinking the British aircraft carrier HMS Courageous. The 22,500 ton light cruiser had been converted to an escort carrier and was being used in an anti submarine warfare role. She was on patrol in the South West Approaches [south west of Ireland] with an escort of four destroyers when two were called away to hunt a U-Boat that was reported to be attacking a merchant ship. At dusk, the carrier's patrolling Swordfish aircraft were due to land and Courageous turned into the wind in preparation to receive the returning aircraft. The two remaining escort destroyers were on station near by. It is possible the U-29 just happened to be in the right place at the right time or was there by good planning. Either way, at approximately 1950, Kapitanleutnant Schuhart wasted no time in exploiting this golden opportunity by firing two torpedoes at the carrier, both scoring hits. Courageous began to sink and disappeared beneath the waves in approximately 20 minutes but managed to send a distress signal to any nearby ships. Kelly’s wireless operator received the SOS and the destroyer raced at full speed to the reported position only to find the carrier had already sunk. The icy sea claimed many unfortunate sailors, others choked to death in the mixed morass of oil and aviation fuel. Many were killed in the initial explosions. The reality of war was a sobering sight to the still raw Kelly crew.

Two nearby neutral ships had also answered the distress call. The Dutch Veendam and the American Collingsworth were already assisting the escort destroyers in the rescue effort. Kelly scoured the area, partially looking for the submarine but also picking up survivors at the same time. After taking off the survivors from the Collingsworth, Lord Mountbatten continued to search the area for another two hours before leaving for Devonport. Hitler was delighted with the news of the sinking and ordered Schuhart and his crew to be awarded the Iron Cross Second Class in recognition of their achievement. The first British Naval loss of the war totalled approximately 518 personal, out of a total complement of 1,200. A devastating blow to England and a great loss to the Royal Navy so early in the war.

9th October 1939. An American ship, the SS City of Flint had been captured in the Atlantic by the German pocket battleship Deutschland. The City of Flint had been en-route from New York to Great Britain carrying 4,000 tons of lubricating oil and became the first American ship to be captured by the Germans during World War 2. Her cargo was declared as ‘contraband’ and was being sent back to Germany as a ‘prize’ ship. Back on September 3, The SS City of Flint had been instrumental in the rescue of 200 survivors from the torpedoed 13,500 ton British passenger liner SS Athenia. Three British destroyers and the freighter, Southern Cross were also involved in the rescue. The U-30’s captain had possibly mistaken the liner for an armed merchant cruiser. There were 1,103 civilians aboard of whom 300 were Americans heading home away from the war zone.

14th October 1939. HMS Kelly was on convoy escort duty in the Channel when one of the ships was struck by a torpedo. The escorting destroyers raced to the suspected position of the U-Boat with Kelly in the lead. A deadly game began between the hunter and the hunted. Mountbatten’s crew got in first with a series of asdic pings and began to pattern depth charge the indicated position of the U-Boat. After a second pattern had been completed, a large spread of oil appeared on the surface. Moments later, the bow of the submarine broke the surface in a cauldron of fuel oil and foam. Then, just as suddenly as it appeared, the bow tilted on a sharp angle and slid backwards beneath the surface. Kelly had scored her first kill. The German submariners were doomed to die in a steel coffin on the ocean floor as would so many more of their ship's comrades throughout WW2.

Towards the end of October, Lord Mountbatten’s destroyer that had been assigned patrol duty in the rough and stormy North Sea and for the most part, it was uneventful until they received information the City of Flint was going to attempt to reach Kiel by way of the Norwegian coastline. Kelly and a group of destroyers were ordered to intercept the American ship before she could reach its destination.

3rd November 1939. Because of the constant pursuit by the Royal Navy destroyers, the Germans were forced to enter the neutral Norwegian port of Bergen and became interned by the Norwegian authorities. Kelly also entered the Norwegian territorial waters in pursuit but was immediately confronted by a small Norwegian gunboat which ordered the Kelly to leave. Lord Mountbatten asked the gunboat captain to give his compliments to his cousin, Crown Prince Olaf and to wish him well then withdrew his ship back into international waters and more patrolling.

Three days later, because the City of Flint was a neutral ship captured illegally by the Germans, the Norwegian authorities interned the German crew and returned the ship back to the American captain, Joseph. A. Gainard and his crew. [ The City of Flint was torpedoed and sunk off the Azores in January 1943.]

As for the Kelly, she was ordered back to the Tyne. She was in need of repairs as the North Sea waves, the wind, wild weather and constant patrolling had taken a toll on both man and ship. Within a month she was looking brand new again and ready for duty.

14th/15th December 1939. The refurbished Kelly accompanied by the destroyer Mohawk were both steaming towards the river mouth of the Tyne when they received a message that two tankers had either been torpedoed or struck a mine 11 miles off the Tyne in the Channel. Both raced to the scene of the two sinking ships, one was in flames. The destroyers separated to pick up any survivors, Captain Mountbatten choosing the burning tanker to come alongside and take off those who were still alive. It was approximately 1630 when Kelly began to manoeuvre into position for the rescue attempt when the crew below the deck of the destroyer heard a series of loud bumps going along the length of the hull. They assumed they had come alongside the tanker when suddenly a loud explosion shook the ship. A mine had scraped Kelly’s side only to explode just past the ships stern. The resulting damage wrenched the stern several feet out of alignment, twisted the propellers and wrecked the engine drive shaft. The Kelly was dead in the water and a sitting duck for any U-Boat than happened to be nearby and cared to take a shot. Two tugs were urgently dispatched to tow the destroyer and one of the tankers back to safety. The Kelly returned to the Hebburn shipyard for repairs. She had only left the day before and here she was back already. The workmen at the Hebburn ship yard were getting to know this ship very well. At least the crew got some shore leave and a chance to spend Christmas with their families. As soon as the repairs were completed, the Kelly was off again.

28th February 1940. This time it was escort duty in Northern waters with the regular diet of howling gales, rough seas, blinding snowstorms and the ever present cold. It’s possible some of the crew wished they had joined the infantry instead of the Navy. Kelly had been assigned escort duty to a northbound convoy which had been experiencing rough weather and the thick gloom of a snowstorm for days on end.

9th March 1940. The convoy ploughed on, visibility was down to almost zero when a Kelly lookout saw a dark shape loom out of the blinding storm off the port bow. Action was immediately taken to avoid a collision but it was too late. The dark shape of HMS Gurkha also took action and swung hard to starboard but her propeller or propeller guard ripped into the Kelly tearing a 30 feet long gash along the bow. The icy North Sea began pouring into the gaping wound. Captain Mountbatten ordered temporary repairs be carried out but he was really left with no choice but to pull out of the convoy and limp home. HMS Gurkha and HMS Nubian had been escorting a convoy in the opposite direction and the outer flank escorts knew nothing of each other's position due to the severity of the snowstorm. Kelly eventually made it back to a graving dock in London for repairs as her usual place at Hebburn was occupied.

29th April 1940. Kelly’s repairs had been speeded up in time for her to be part of a naval rescue force from Scapa Flow racing towards the Norwegian port of Namsos. A small Allied force including a contingent of French Chasseurs Alpins were to be evacuated from the beleaguered town as the Germans were rapidly closing in. With Denmark submitting to German occupation without firing a shot, Norway bravely resisted the invader who needed the country for aircraft operations against the British Isles and to break the Royal Navy blockade of Swedish iron ore so vital to Germany’s heavy industry. The British sent a small force to assist the Norwegians but it was a gesture doomed to failure. Without air protection, they were bombed incessantly. The Allied forces Commander, General de Wiart received orders for a general evacuation scheduled for 1-2 May from Namos.

Ist May 1940. The British rescue force comprising warships and transports were bombed en-route but arrived on schedule in the afternoon but had to stop eighty miles short of the rendezvous point due to thick fog. Evacuation that night was out of the question and it was cancelled. On hearing the news of the cancellation, the tired and dispirited soldiers waiting at the Namos quayside began to disperse until the following night. Suddenly, like a ghostly apparition the bow of a destroyer edged its way out of the fog into the clear night over Namos. More followed. Captain Mountbatten had brought Kelly and his flotilla through the seventy miles of treacherous rocky Norwegian coastline, dodging from fog cover to fog cover, through the fiord entrance and dashed up the narrow waterway to the besieged town. Any euphoria the sailors or soldiers had about the moment were shattered by the appearance of the German bombers that been harassing the ships rescue dash through the fog. Evacuation was out of the question under the circumstances. The ships disappeared back into the fog and back to the open sea. Mountbatten had convinced his superiors that if the fog hid the Germans from them, the fog would also hide them from the Germans and asked permission to attempt the rescue. It was a valiant attempt fraught with disaster but it had worked spoilt only by the presence of the Luftwaffe.

2nd May 1940. The last day of the rescue and the ships were still fogbound. By the evening the situation was becoming desperate. Suddenly as if by a miracle, the fog cleared for about 40 miles to the fiord entrance. It was going to be a close thing but with Kelly leading, the destroyers and transport ships raced for Namos. They had started loading in the light of the burning town at approximately 2230 and were away by 0220 the next morning. The ever present Luftwaffe spotted the rear of the retreating group two hours later and like a swarm of angry bees, attacked constantly until late that afternoon. The French destroyer, Bison was left a burning wreck. Afridi was hit and capsized with loss of about 100 crew. Other ships stopped to pick up survivors at great risk then rushed to continue the exodus to the safety of Scapa Flow. As soon as the troops had been safely landed at Scapa Flow, the destroyers were ordered to escort the empty transport ships back to the Clyde. If the tired and exhausted crews thought a bit of shore leave was due, they were sadly mistaken. Within hours they were back at sea again.

9th May 1940. Kelly was leading a destroyer flotilla to assist the cruiser Birmingham and her escorts Janus, Hyperion, Hereward, Havock and Hostile hunt and hopefully destroy a flotilla of E-Boats or Schnellboot [German motor torpedo boats] that were protecting some minelayers operating in the Skagerrak in the North Sea. At around 1800 an escorting reconnaissance aircraft reported a U-Boat sighting ahead of the ship's current position. Both Kelly and Kandahar left the group and went in pursuit of the submarine. Depth charges were dropped on the reported position with negative results. Further action had to be called off as the two destroyers had lost sight of the Birmingham and her escorts so both left at full speed to regain their place in the group. A German bomber was sighted and driven off by anti aircraft fire. The bomber retired to a safe distance to keep the ships under surveillance and possibly report their position to the nearby E-Boats.

At approximately 2025, Oberleutnant zur See Hermann Opdenhoff in E-boat S31 of 3 MTB Flotilla launched one possibly two torpedoes at the Kelly. A lookout aboard Kelly had observed a dark shape about 600 yards on the port bow and saw the wake of a torpedo approaching but it was too late to take any evasive action. The torpedo hit the forward boiler room and exploded with disastrous results. Dead and dying crew were strewn all around the gaping wound in Kelly’s side. The boiler had been ripped from its fixture and tossed to starboard sending boiling hot steam spewing everywhere. After the initial shock of the explosion had worn off, the stunned crew swung into action. As the ship began to list badly to starboard, damage control crews went to work removing anything moveable to prevent her possibly capsizing. Torpedoes were ‘set to sink’ then fired, depth charges ‘set to safe’ then ‘ready’ ammunition jettisoned and any portable fixtures were thrown overboard. Life boats were lowered in preparation to abandon ship. With no power available except for emergency lighting facilities, Kelly seemed lifeless and doomed.

No one had abandoned ship nor was the order given. Captain Mountbatten was going to do his best to try and save his ship and his crew. Fortunately, out of the gloom appeared Bulldog and positioned herself alongside the stricken Kelly. After several attempts to attach a towline in the dark with both ships pitching in the rough seas, Bulldog finally managed to secure the towline and began the difficult job of towing the Kelly back to port. The enemy E-Boat had disappeared. Where possible, the dead and wounded were located amongst the twisted tangle of wreckage. The ships surgeon worked wonders under horrendous conditions with the injured.

10th May 1940. In the early morning light, Kandahar took off the wounded and her doctor continued treating the wounded. Also with the dawn came the grisly job of recovering the bodies of shipmates unable to be located during the night. Short burial services were conducted and the bodies consigned to the deep. By now, other destroyers had arrived and were ordered to form an anti submarine and anti aircraft defensive screen around Bulldog and Kelly. The destroyers were paid a visit by German bombers but were driven off by the combined firepower of the group. To make things even more difficult, the weather began to worsen making the Kelly’s list more pronounced and her movements very difficult and sluggish. Fearing she would capsize at any moment, Captain Mountbatten estimated the weight needed to keep her at her present angle. He then ordered the crew equal to his calculated weight to be transferred to other destroyers but retained a volunteer skeleton crew.

11th May 1940. The Luftwaffe returned for another attack on the group and was repulsed again. Throughout the day, the towline broke repeatedly but was always repaired under difficult circumstances. At nightfall, two U-Boats were reported to be closing in so all the volunteer crew were transferred temporarily to Bulldog effectively abandoning the waterlogged destroyer for the night.

12th May 1940. At dawn, the skeleton crew rejoined their beloved ship and the tow got underway again. Yet again the German bombers came back and again they had to leave without scoring a hit. When night-time finally arrived, it gave the ship's officers and crew a much needed respite as the darkness enveloped the group in its inky blackness.

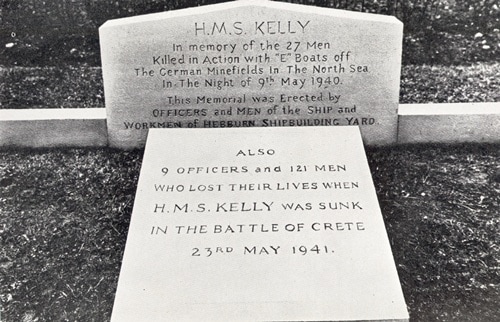

13th May 1940. It had been a harrowing time fighting the sea, the Luftwaffe and the possibility of the Kelly giving up her fight to stay afloat and slip beneath the waves. But that afternoon after 92 hours in tow, H.M.S Kelly eventually arrived home at the Hebburn ship yard. With the ship in dry dock and the water drained out, everyone who saw the extent of the damage were amazed she survived. The adoption of Mr Cole’s new design and the workmanship of her builders were the only things that prevented her from breaking in two. It was also estimated that had the extra weight [crew] not been removed when they were, the Kelly would have capsized. In a tribute to the men who built her, the Royal Navy Controller wrote a report that her survival was achieved not only by good seamanship by the officers and men but also on account of the excellent workmanship which ensured the watertightness of the compartments. He also said, ‘A single defective rivet may have finished her.’ A few undiscovered bodies were found amongst the mangled wreckage and buried in the Hebburn Cemetery. Thousands came to a memorial service to pay tribute to the brave officers and crew of the Kelly who died. A commemorative tablet was erected in their honour.

17th September 1939. This was an evening Kapitanleutnant Otto Schuhart and the crew of U-Boat 29 would never forget. They had just scored the first major U-Boat success of the war by sinking the British aircraft carrier HMS Courageous. The 22,500 ton light cruiser had been converted to an escort carrier and was being used in an anti submarine warfare role. She was on patrol in the South West Approaches [south west of Ireland] with an escort of four destroyers when two were called away to hunt a U-Boat that was reported to be attacking a merchant ship. At dusk, the carrier's patrolling Swordfish aircraft were due to land and Courageous turned into the wind in preparation to receive the returning aircraft. The two remaining escort destroyers were on station near by. It is possible the U-29 just happened to be in the right place at the right time or was there by good planning. Either way, at approximately 1950, Kapitanleutnant Schuhart wasted no time in exploiting this golden opportunity by firing two torpedoes at the carrier, both scoring hits. Courageous began to sink and disappeared beneath the waves in approximately 20 minutes but managed to send a distress signal to any nearby ships. Kelly’s wireless operator received the SOS and the destroyer raced at full speed to the reported position only to find the carrier had already sunk. The icy sea claimed many unfortunate sailors, others choked to death in the mixed morass of oil and aviation fuel. Many were killed in the initial explosions. The reality of war was a sobering sight to the still raw Kelly crew.

Two nearby neutral ships had also answered the distress call. The Dutch Veendam and the American Collingsworth were already assisting the escort destroyers in the rescue effort. Kelly scoured the area, partially looking for the submarine but also picking up survivors at the same time. After taking off the survivors from the Collingsworth, Lord Mountbatten continued to search the area for another two hours before leaving for Devonport. Hitler was delighted with the news of the sinking and ordered Schuhart and his crew to be awarded the Iron Cross Second Class in recognition of their achievement. The first British Naval loss of the war totalled approximately 518 personal, out of a total complement of 1,200. A devastating blow to England and a great loss to the Royal Navy so early in the war.

9th October 1939. An American ship, the SS City of Flint had been captured in the Atlantic by the German pocket battleship Deutschland. The City of Flint had been en-route from New York to Great Britain carrying 4,000 tons of lubricating oil and became the first American ship to be captured by the Germans during World War 2. Her cargo was declared as ‘contraband’ and was being sent back to Germany as a ‘prize’ ship. Back on September 3, The SS City of Flint had been instrumental in the rescue of 200 survivors from the torpedoed 13,500 ton British passenger liner SS Athenia. Three British destroyers and the freighter, Southern Cross were also involved in the rescue. The U-30’s captain had possibly mistaken the liner for an armed merchant cruiser. There were 1,103 civilians aboard of whom 300 were Americans heading home away from the war zone.

14th October 1939. HMS Kelly was on convoy escort duty in the Channel when one of the ships was struck by a torpedo. The escorting destroyers raced to the suspected position of the U-Boat with Kelly in the lead. A deadly game began between the hunter and the hunted. Mountbatten’s crew got in first with a series of asdic pings and began to pattern depth charge the indicated position of the U-Boat. After a second pattern had been completed, a large spread of oil appeared on the surface. Moments later, the bow of the submarine broke the surface in a cauldron of fuel oil and foam. Then, just as suddenly as it appeared, the bow tilted on a sharp angle and slid backwards beneath the surface. Kelly had scored her first kill. The German submariners were doomed to die in a steel coffin on the ocean floor as would so many more of their ship's comrades throughout WW2.

Towards the end of October, Lord Mountbatten’s destroyer that had been assigned patrol duty in the rough and stormy North Sea and for the most part, it was uneventful until they received information the City of Flint was going to attempt to reach Kiel by way of the Norwegian coastline. Kelly and a group of destroyers were ordered to intercept the American ship before she could reach its destination.

3rd November 1939. Because of the constant pursuit by the Royal Navy destroyers, the Germans were forced to enter the neutral Norwegian port of Bergen and became interned by the Norwegian authorities. Kelly also entered the Norwegian territorial waters in pursuit but was immediately confronted by a small Norwegian gunboat which ordered the Kelly to leave. Lord Mountbatten asked the gunboat captain to give his compliments to his cousin, Crown Prince Olaf and to wish him well then withdrew his ship back into international waters and more patrolling.

Three days later, because the City of Flint was a neutral ship captured illegally by the Germans, the Norwegian authorities interned the German crew and returned the ship back to the American captain, Joseph. A. Gainard and his crew. [ The City of Flint was torpedoed and sunk off the Azores in January 1943.]

As for the Kelly, she was ordered back to the Tyne. She was in need of repairs as the North Sea waves, the wind, wild weather and constant patrolling had taken a toll on both man and ship. Within a month she was looking brand new again and ready for duty.

14th/15th December 1939. The refurbished Kelly accompanied by the destroyer Mohawk were both steaming towards the river mouth of the Tyne when they received a message that two tankers had either been torpedoed or struck a mine 11 miles off the Tyne in the Channel. Both raced to the scene of the two sinking ships, one was in flames. The destroyers separated to pick up any survivors, Captain Mountbatten choosing the burning tanker to come alongside and take off those who were still alive. It was approximately 1630 when Kelly began to manoeuvre into position for the rescue attempt when the crew below the deck of the destroyer heard a series of loud bumps going along the length of the hull. They assumed they had come alongside the tanker when suddenly a loud explosion shook the ship. A mine had scraped Kelly’s side only to explode just past the ships stern. The resulting damage wrenched the stern several feet out of alignment, twisted the propellers and wrecked the engine drive shaft. The Kelly was dead in the water and a sitting duck for any U-Boat than happened to be nearby and cared to take a shot. Two tugs were urgently dispatched to tow the destroyer and one of the tankers back to safety. The Kelly returned to the Hebburn shipyard for repairs. She had only left the day before and here she was back already. The workmen at the Hebburn ship yard were getting to know this ship very well. At least the crew got some shore leave and a chance to spend Christmas with their families. As soon as the repairs were completed, the Kelly was off again.

28th February 1940. This time it was escort duty in Northern waters with the regular diet of howling gales, rough seas, blinding snowstorms and the ever present cold. It’s possible some of the crew wished they had joined the infantry instead of the Navy. Kelly had been assigned escort duty to a northbound convoy which had been experiencing rough weather and the thick gloom of a snowstorm for days on end.

9th March 1940. The convoy ploughed on, visibility was down to almost zero when a Kelly lookout saw a dark shape loom out of the blinding storm off the port bow. Action was immediately taken to avoid a collision but it was too late. The dark shape of HMS Gurkha also took action and swung hard to starboard but her propeller or propeller guard ripped into the Kelly tearing a 30 feet long gash along the bow. The icy North Sea began pouring into the gaping wound. Captain Mountbatten ordered temporary repairs be carried out but he was really left with no choice but to pull out of the convoy and limp home. HMS Gurkha and HMS Nubian had been escorting a convoy in the opposite direction and the outer flank escorts knew nothing of each other's position due to the severity of the snowstorm. Kelly eventually made it back to a graving dock in London for repairs as her usual place at Hebburn was occupied.

29th April 1940. Kelly’s repairs had been speeded up in time for her to be part of a naval rescue force from Scapa Flow racing towards the Norwegian port of Namsos. A small Allied force including a contingent of French Chasseurs Alpins were to be evacuated from the beleaguered town as the Germans were rapidly closing in. With Denmark submitting to German occupation without firing a shot, Norway bravely resisted the invader who needed the country for aircraft operations against the British Isles and to break the Royal Navy blockade of Swedish iron ore so vital to Germany’s heavy industry. The British sent a small force to assist the Norwegians but it was a gesture doomed to failure. Without air protection, they were bombed incessantly. The Allied forces Commander, General de Wiart received orders for a general evacuation scheduled for 1-2 May from Namos.

Ist May 1940. The British rescue force comprising warships and transports were bombed en-route but arrived on schedule in the afternoon but had to stop eighty miles short of the rendezvous point due to thick fog. Evacuation that night was out of the question and it was cancelled. On hearing the news of the cancellation, the tired and dispirited soldiers waiting at the Namos quayside began to disperse until the following night. Suddenly, like a ghostly apparition the bow of a destroyer edged its way out of the fog into the clear night over Namos. More followed. Captain Mountbatten had brought Kelly and his flotilla through the seventy miles of treacherous rocky Norwegian coastline, dodging from fog cover to fog cover, through the fiord entrance and dashed up the narrow waterway to the besieged town. Any euphoria the sailors or soldiers had about the moment were shattered by the appearance of the German bombers that been harassing the ships rescue dash through the fog. Evacuation was out of the question under the circumstances. The ships disappeared back into the fog and back to the open sea. Mountbatten had convinced his superiors that if the fog hid the Germans from them, the fog would also hide them from the Germans and asked permission to attempt the rescue. It was a valiant attempt fraught with disaster but it had worked spoilt only by the presence of the Luftwaffe.

2nd May 1940. The last day of the rescue and the ships were still fogbound. By the evening the situation was becoming desperate. Suddenly as if by a miracle, the fog cleared for about 40 miles to the fiord entrance. It was going to be a close thing but with Kelly leading, the destroyers and transport ships raced for Namos. They had started loading in the light of the burning town at approximately 2230 and were away by 0220 the next morning. The ever present Luftwaffe spotted the rear of the retreating group two hours later and like a swarm of angry bees, attacked constantly until late that afternoon. The French destroyer, Bison was left a burning wreck. Afridi was hit and capsized with loss of about 100 crew. Other ships stopped to pick up survivors at great risk then rushed to continue the exodus to the safety of Scapa Flow. As soon as the troops had been safely landed at Scapa Flow, the destroyers were ordered to escort the empty transport ships back to the Clyde. If the tired and exhausted crews thought a bit of shore leave was due, they were sadly mistaken. Within hours they were back at sea again.

9th May 1940. Kelly was leading a destroyer flotilla to assist the cruiser Birmingham and her escorts Janus, Hyperion, Hereward, Havock and Hostile hunt and hopefully destroy a flotilla of E-Boats or Schnellboot [German motor torpedo boats] that were protecting some minelayers operating in the Skagerrak in the North Sea. At around 1800 an escorting reconnaissance aircraft reported a U-Boat sighting ahead of the ship's current position. Both Kelly and Kandahar left the group and went in pursuit of the submarine. Depth charges were dropped on the reported position with negative results. Further action had to be called off as the two destroyers had lost sight of the Birmingham and her escorts so both left at full speed to regain their place in the group. A German bomber was sighted and driven off by anti aircraft fire. The bomber retired to a safe distance to keep the ships under surveillance and possibly report their position to the nearby E-Boats.

At approximately 2025, Oberleutnant zur See Hermann Opdenhoff in E-boat S31 of 3 MTB Flotilla launched one possibly two torpedoes at the Kelly. A lookout aboard Kelly had observed a dark shape about 600 yards on the port bow and saw the wake of a torpedo approaching but it was too late to take any evasive action. The torpedo hit the forward boiler room and exploded with disastrous results. Dead and dying crew were strewn all around the gaping wound in Kelly’s side. The boiler had been ripped from its fixture and tossed to starboard sending boiling hot steam spewing everywhere. After the initial shock of the explosion had worn off, the stunned crew swung into action. As the ship began to list badly to starboard, damage control crews went to work removing anything moveable to prevent her possibly capsizing. Torpedoes were ‘set to sink’ then fired, depth charges ‘set to safe’ then ‘ready’ ammunition jettisoned and any portable fixtures were thrown overboard. Life boats were lowered in preparation to abandon ship. With no power available except for emergency lighting facilities, Kelly seemed lifeless and doomed.

No one had abandoned ship nor was the order given. Captain Mountbatten was going to do his best to try and save his ship and his crew. Fortunately, out of the gloom appeared Bulldog and positioned herself alongside the stricken Kelly. After several attempts to attach a towline in the dark with both ships pitching in the rough seas, Bulldog finally managed to secure the towline and began the difficult job of towing the Kelly back to port. The enemy E-Boat had disappeared. Where possible, the dead and wounded were located amongst the twisted tangle of wreckage. The ships surgeon worked wonders under horrendous conditions with the injured.

10th May 1940. In the early morning light, Kandahar took off the wounded and her doctor continued treating the wounded. Also with the dawn came the grisly job of recovering the bodies of shipmates unable to be located during the night. Short burial services were conducted and the bodies consigned to the deep. By now, other destroyers had arrived and were ordered to form an anti submarine and anti aircraft defensive screen around Bulldog and Kelly. The destroyers were paid a visit by German bombers but were driven off by the combined firepower of the group. To make things even more difficult, the weather began to worsen making the Kelly’s list more pronounced and her movements very difficult and sluggish. Fearing she would capsize at any moment, Captain Mountbatten estimated the weight needed to keep her at her present angle. He then ordered the crew equal to his calculated weight to be transferred to other destroyers but retained a volunteer skeleton crew.

11th May 1940. The Luftwaffe returned for another attack on the group and was repulsed again. Throughout the day, the towline broke repeatedly but was always repaired under difficult circumstances. At nightfall, two U-Boats were reported to be closing in so all the volunteer crew were transferred temporarily to Bulldog effectively abandoning the waterlogged destroyer for the night.

12th May 1940. At dawn, the skeleton crew rejoined their beloved ship and the tow got underway again. Yet again the German bombers came back and again they had to leave without scoring a hit. When night-time finally arrived, it gave the ship's officers and crew a much needed respite as the darkness enveloped the group in its inky blackness.

13th May 1940. It had been a harrowing time fighting the sea, the Luftwaffe and the possibility of the Kelly giving up her fight to stay afloat and slip beneath the waves. But that afternoon after 92 hours in tow, H.M.S Kelly eventually arrived home at the Hebburn ship yard. With the ship in dry dock and the water drained out, everyone who saw the extent of the damage were amazed she survived. The adoption of Mr Cole’s new design and the workmanship of her builders were the only things that prevented her from breaking in two. It was also estimated that had the extra weight [crew] not been removed when they were, the Kelly would have capsized. In a tribute to the men who built her, the Royal Navy Controller wrote a report that her survival was achieved not only by good seamanship by the officers and men but also on account of the excellent workmanship which ensured the watertightness of the compartments. He also said, ‘A single defective rivet may have finished her.’ A few undiscovered bodies were found amongst the mangled wreckage and buried in the Hebburn Cemetery. Thousands came to a memorial service to pay tribute to the brave officers and crew of the Kelly who died. A commemorative tablet was erected in their honour.

During the months it took to rebuild Kelly, the war had worsened for the Allies. The Battle of Britain was being fought out with grim determination by young German and Allied pilots for control of the skies over England. Nazi bombers hammered the English cities and industrial infrastructure, France fell to the German blitzkrieg and a demoralised British Army waited to be evacuated from a French seaside town called Dunkirk. Every available destroyer was needed to rescue the soldiers.

28th May- 4th June 1940. A conglomeration of 850 British vessels of all sizes and shapes and propulsion-mostly manned by civilian volunteers-converged on Dunkirk to begin the most amazing exodus in history. In 8 days, more than 338,000 men- among them 112,000 French and Belgian soldiers were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk. Nine destroyers were sunk and 23 badly damaged in the face of constant air attacks by a determined Luftwaffe bent on sending all enemies of the Reich to hell. This was one battle the Kelly had to miss out on as it was seven months before she was ready for duty again.

December 1940. Because of the massive repair work, she had to undergo all the shakedown trials again and allow time for the replacement crew to learn the ropes. One new man who was to have an impact on the ship's officers and crew was Captain Mountbatten’s new First Lieutenant, Lord Hugh Tristian de la Poer Beresford. He became a source of strength and inspiration to all aboard the ship. His faith as a devout Christian and his shy but loveable personality endeared him to all ranks regardless of their religious conviction and without class distinction which was still very much alive and well in England at the time. He clearly saw the war as a crusade of good against evil and as a professional navy man who, apart from the Captain, would supervise their daily lives.

26th April 1941. As a small British force of ships including the cruiser Dido, the minelayer Abdiel and destroyers of 5th Flotilla including Kelly were steaming towards Malta, the last radio broadcast was made from the Greek capital, Athens. Allied resistance had collapsed and Greece was now under the iron fisted rule of the Nazi invader. The naval force had been ordered to the Grand Harbour of Valetta in Malta [known as Britain’s unsinkable aircraft carrier] as replacements for the Mediterranean fleet. After a few months of convoy work, chasing German battleships, escorting and general duties, the ships' crews looked forward with eager anticipation that they might get a bit of shore leave and taste the delights the Mediterranean island of Malta had to offer. Swimming, booze, dance halls, warm sunshine and of course the alluring charms of the ladies. No sooner had they berthed all thoughts of women and booze were quickly forgotten. German Stukas arrived to welcome the Flotilla with a rain of bombs. Malta had changed a little since some of the sailor’s last visit. The Luftwaffe was bent on reducing the whole island to rubble while the too few RAF fighters were equally determined to stop them. Kelly’s main assignment was to carry out nightly sweeps against any enemy ships attempting to supply Rommel’s Army in Africa. Kelly and Lord Mountbatten’s ‘gang of pirates’ as one ship's crew affectionately called them, was one of several ships assigned the job of bombarding the Axis held harbour of Benghazi in Libya. The harbour and dock installations were an important supply line to Rommel’s Afrika Korps and any disruption to this flow of his vital war materials would greatly assist the Allied Army in Africa.

7th/8th May 1941. On the night of this operation, the sky was bathed in bright moonlight and the destroyers steamed towards their target in two groups about a mile apart. Once they had reached a pre-arranged position, they would open fire. Ammunition expenditure was to be 200 rounds of high explosive with the 4 inch guns to fire starshell to illuminate the target. By extremely good fortune, the destroyers were not spotted. Once at the correct location, both groups opened fire at the enemy ships inside the protected harbour. As soon as the shore batteries began to return fire, the flotilla began a quick strategic withdrawal using smoke to cover their departure and set a course back to Malta. They had left behind two burning and sinking wrecks and a seriously disrupted the German/Italian supply line. Enemy aircraft attacked the retreating flotilla but were beaten off without any serious damage to the ships. With the loss of Greece, British, Australian, New Zealand and Greek troops were evacuated and sent to Crete where it was thought the next German assault would take place. They were joined by reinforcements from Egypt to bolster the island's defences. It was a correct assessment as the German Air Force began carrying out bombing attacks on Crete almost daily.

20th May 1941. After an exceptionally heavy aerial bombardment, units of the 7th Fallschirmjäger [Paratroop] Division began a massive airborne invasion of Crete initially aimed at the capture of the three airports, Herakleion, Malene and Rethymnon. The defenders inflicted massive casualties on the enemy but regardless of their losses, the Germans managed to gain partial control of the Malene airport. This allowed elements of the 5th Mountain Division to begin landing further troops. Most of the aircraft were destroyed but enough got through to allow the German reinforcements to assist the 7th Division to hold the airfield allowing even more help to arrive. The defenders fought with bitter determination but were eventually forced to withdraw to the south coast and evacuation by the Royal Navy from the coastal town of Sfakia. The Royal Navy managed to rescue approximately 15,000 soldiers from Crete between 27-28 May but at a high cost in men and ships. Those units that were cut off by the German advance were forced to surrender.

21st May 1941. It was vital the navy prevented a sea borne landing on Crete so Kelly and four other destroyers were ordered from Malta to join the rest of the fleet west of Crete.

22nd May 1941. By the afternoon they had arrived but at 1856, Kelly received orders to proceed to Canea Bay and shell the Maleme airfield. Kelly set out with Kipling and Kashmir to carry out their assignment. Kipling had to withdraw due to defective steering gear. As they entered Canea Bay, Kelly’s radar picked up two echoes bearing Red 80, Range 030. Both Kashmir and Kelly opened their searchlights onto the targets revealing two fishing boats jammed full of heavily armed German troops. Both destroyers opened fire and sunk both enemy boats and killed most of the unfortunate soldiers. Many would have drowned with the weight of a full pack. The unpleasant duty of killing over, the destroyers continued on to a point off shore and began to rain shells onto the Maleme airstrip. With their mission completed, Captain Mountbatten was ordered to withdraw at high speed towards Alexandria to refuel and rearm. As they were leaving the bay, they spotted another enemy ship carrying either ammunition or aviation fuel. It was also destroyed with spectacular results. Another reason for the withdrawal was the expected retaliation by enemy aircraft therefore it would be better to be closer to the protection of the fleet's combined firepower when the enemy aircraft arrived.

23rd May 1941. As both destroyers steamed south down the coast of Crete a German reconnaissance aircraft was reporting their position to Headquarters. Captain Mountbatten in a later account of the action to his sister Louise, Queen of Sweden wrote; ‘As the sun rose, a German Dornier 215 appeared out of the east and was engaged before she dropped five bombs which missed Kelly astern. Forty minutes later, three more Do 215s made a high level bombing attack on Kelly and Kashmir. Both ships avoided the bombs. I sent for my breakfast on the bridge and I continued reading C.S.Forester’s book about my favourite hero Hornblower called, Ship of the Line.’

It was approximately 0800 when the black angels of death in the form of twenty four Stukas from General Wolfram von Richthofen’s V111 Air Corps screamed out of the sky and attacked the retreating destroyers. The Stukas had a fearsome reputation for diving almost vertically on ships and only releasing their bombs when they were so low that they couldn’t miss. Kashmir was hit amidships by two bombs, her magazine exploded and she sank within two minutes. One Stuka came in lower than the rest over Kelly and released its bomb hitting square on X gun-deck killing the gun crew. Kelly’s gunners kept up a barrage of fire against the attacking aircraft but another bomb exploded right beside the Kelly tearing a gaping hole in her side near X magazine while she was still steaming at 30 knots. The destroyer lost its stability and began rolling over at speed eventually capsizing but still continuing its forward momentum. She finally stopped all movement and for a while floated upside down with the length of her keel from stem to stern exposed. The screws were still turning while several of her crew clung precariously to the keel. All around the mortally wounded ship were men struggling to survive in a sea covered in a stinking thick mixture of fuel oil and debris. Some were killed in the initial blast; some drowned when the Kelly capsized or choked to death, their lungs full of oil or were killed when the Stukas returned to machine gun the struggling survivors.

Kelly finally tilted on an angle and slowly sank beneath the surface. Her brief but eventful life finally at an end. Perhaps those who watched her go possibly remembered lost shipmates, friends and a ship they had the honour and privilege to serve aboard. Survivors from both the Kelly and the Kashmir were clinging onto life amongst the wreckage of war. The situation looked hopeless. A few gave up and quietly slipped under the water, others fought the grim reaper with every ounce of their being. Captain Mountbatten and Lieutenant-Commander Beresford rescued many injured crew, swimming to someone in difficulty and getting him to the safety of a raft or piece of floating debris.

A ship was sighted heading towards them at full speed. Kipling came straight away, her defective steering finally repaired. The crew threw overboard to the men in the water anything that would float and lowered the scrambling nets over the sides. While they attempted to rescue the stricken sailors, the Germans persisted with their attacks on the men in the water and on the Kipling. Included among the rescued were Lord Mountbatten and his Lieutenant-Commander, Hugh Beresford. As Captain of the flotilla, Mountbatten took charge of the Kipling and the rescue operations. He immediately ordered the motorised life boat lowered into the water to assist in the rescue. As soon as the boat touched the water the Stukas attacked the Kipling again. The destroyer's 40,000 horsepower engine powering the destroyer forward in a surge of speed making it difficult to be hit. Unfortunately, the motor boat had not been released from the davit and this valuable rescue tool was being dragged under the sea bow first. Captain Mountbatten shouted out an order for someone to cut the after falls. Only First Lieutenant Beresford and the Kipling’s First Lieutenant John Bushe heard his order. Both immediately leapt to the after falls at the very moment the ship gathered speed. The heavy motorboat had sunk so deep in the water that the ship's speed wrenched the davit from its mooring taking the two officers with it and killing them both.

The slow and dangerous process of rescuing the helpless survivors under constant attack from the Luftwaffe continued but approximately three hours later, after having rescued some 279 officers and men, Kipling finally set a course for Alexandria 400 miles away. The Germans gave up trying to sink the ship allowing the Kipling to steam on through the night unmolested. At dawn, they ran out of fuel but Protector came out from Alexandria and replenished her fuel tanks. With great joy, the exhausted men saw the coast of Egypt and were soon entering the safety of Alexandria harbour. First Lieutenant Beresford’s body was washed up on the North African coast near Sollum a few days later and was buried there. He now rests in peace in the El Alamein Cemetery.

28th May- 4th June 1940. A conglomeration of 850 British vessels of all sizes and shapes and propulsion-mostly manned by civilian volunteers-converged on Dunkirk to begin the most amazing exodus in history. In 8 days, more than 338,000 men- among them 112,000 French and Belgian soldiers were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk. Nine destroyers were sunk and 23 badly damaged in the face of constant air attacks by a determined Luftwaffe bent on sending all enemies of the Reich to hell. This was one battle the Kelly had to miss out on as it was seven months before she was ready for duty again.

December 1940. Because of the massive repair work, she had to undergo all the shakedown trials again and allow time for the replacement crew to learn the ropes. One new man who was to have an impact on the ship's officers and crew was Captain Mountbatten’s new First Lieutenant, Lord Hugh Tristian de la Poer Beresford. He became a source of strength and inspiration to all aboard the ship. His faith as a devout Christian and his shy but loveable personality endeared him to all ranks regardless of their religious conviction and without class distinction which was still very much alive and well in England at the time. He clearly saw the war as a crusade of good against evil and as a professional navy man who, apart from the Captain, would supervise their daily lives.

26th April 1941. As a small British force of ships including the cruiser Dido, the minelayer Abdiel and destroyers of 5th Flotilla including Kelly were steaming towards Malta, the last radio broadcast was made from the Greek capital, Athens. Allied resistance had collapsed and Greece was now under the iron fisted rule of the Nazi invader. The naval force had been ordered to the Grand Harbour of Valetta in Malta [known as Britain’s unsinkable aircraft carrier] as replacements for the Mediterranean fleet. After a few months of convoy work, chasing German battleships, escorting and general duties, the ships' crews looked forward with eager anticipation that they might get a bit of shore leave and taste the delights the Mediterranean island of Malta had to offer. Swimming, booze, dance halls, warm sunshine and of course the alluring charms of the ladies. No sooner had they berthed all thoughts of women and booze were quickly forgotten. German Stukas arrived to welcome the Flotilla with a rain of bombs. Malta had changed a little since some of the sailor’s last visit. The Luftwaffe was bent on reducing the whole island to rubble while the too few RAF fighters were equally determined to stop them. Kelly’s main assignment was to carry out nightly sweeps against any enemy ships attempting to supply Rommel’s Army in Africa. Kelly and Lord Mountbatten’s ‘gang of pirates’ as one ship's crew affectionately called them, was one of several ships assigned the job of bombarding the Axis held harbour of Benghazi in Libya. The harbour and dock installations were an important supply line to Rommel’s Afrika Korps and any disruption to this flow of his vital war materials would greatly assist the Allied Army in Africa.

7th/8th May 1941. On the night of this operation, the sky was bathed in bright moonlight and the destroyers steamed towards their target in two groups about a mile apart. Once they had reached a pre-arranged position, they would open fire. Ammunition expenditure was to be 200 rounds of high explosive with the 4 inch guns to fire starshell to illuminate the target. By extremely good fortune, the destroyers were not spotted. Once at the correct location, both groups opened fire at the enemy ships inside the protected harbour. As soon as the shore batteries began to return fire, the flotilla began a quick strategic withdrawal using smoke to cover their departure and set a course back to Malta. They had left behind two burning and sinking wrecks and a seriously disrupted the German/Italian supply line. Enemy aircraft attacked the retreating flotilla but were beaten off without any serious damage to the ships. With the loss of Greece, British, Australian, New Zealand and Greek troops were evacuated and sent to Crete where it was thought the next German assault would take place. They were joined by reinforcements from Egypt to bolster the island's defences. It was a correct assessment as the German Air Force began carrying out bombing attacks on Crete almost daily.

20th May 1941. After an exceptionally heavy aerial bombardment, units of the 7th Fallschirmjäger [Paratroop] Division began a massive airborne invasion of Crete initially aimed at the capture of the three airports, Herakleion, Malene and Rethymnon. The defenders inflicted massive casualties on the enemy but regardless of their losses, the Germans managed to gain partial control of the Malene airport. This allowed elements of the 5th Mountain Division to begin landing further troops. Most of the aircraft were destroyed but enough got through to allow the German reinforcements to assist the 7th Division to hold the airfield allowing even more help to arrive. The defenders fought with bitter determination but were eventually forced to withdraw to the south coast and evacuation by the Royal Navy from the coastal town of Sfakia. The Royal Navy managed to rescue approximately 15,000 soldiers from Crete between 27-28 May but at a high cost in men and ships. Those units that were cut off by the German advance were forced to surrender.

21st May 1941. It was vital the navy prevented a sea borne landing on Crete so Kelly and four other destroyers were ordered from Malta to join the rest of the fleet west of Crete.

22nd May 1941. By the afternoon they had arrived but at 1856, Kelly received orders to proceed to Canea Bay and shell the Maleme airfield. Kelly set out with Kipling and Kashmir to carry out their assignment. Kipling had to withdraw due to defective steering gear. As they entered Canea Bay, Kelly’s radar picked up two echoes bearing Red 80, Range 030. Both Kashmir and Kelly opened their searchlights onto the targets revealing two fishing boats jammed full of heavily armed German troops. Both destroyers opened fire and sunk both enemy boats and killed most of the unfortunate soldiers. Many would have drowned with the weight of a full pack. The unpleasant duty of killing over, the destroyers continued on to a point off shore and began to rain shells onto the Maleme airstrip. With their mission completed, Captain Mountbatten was ordered to withdraw at high speed towards Alexandria to refuel and rearm. As they were leaving the bay, they spotted another enemy ship carrying either ammunition or aviation fuel. It was also destroyed with spectacular results. Another reason for the withdrawal was the expected retaliation by enemy aircraft therefore it would be better to be closer to the protection of the fleet's combined firepower when the enemy aircraft arrived.

23rd May 1941. As both destroyers steamed south down the coast of Crete a German reconnaissance aircraft was reporting their position to Headquarters. Captain Mountbatten in a later account of the action to his sister Louise, Queen of Sweden wrote; ‘As the sun rose, a German Dornier 215 appeared out of the east and was engaged before she dropped five bombs which missed Kelly astern. Forty minutes later, three more Do 215s made a high level bombing attack on Kelly and Kashmir. Both ships avoided the bombs. I sent for my breakfast on the bridge and I continued reading C.S.Forester’s book about my favourite hero Hornblower called, Ship of the Line.’

It was approximately 0800 when the black angels of death in the form of twenty four Stukas from General Wolfram von Richthofen’s V111 Air Corps screamed out of the sky and attacked the retreating destroyers. The Stukas had a fearsome reputation for diving almost vertically on ships and only releasing their bombs when they were so low that they couldn’t miss. Kashmir was hit amidships by two bombs, her magazine exploded and she sank within two minutes. One Stuka came in lower than the rest over Kelly and released its bomb hitting square on X gun-deck killing the gun crew. Kelly’s gunners kept up a barrage of fire against the attacking aircraft but another bomb exploded right beside the Kelly tearing a gaping hole in her side near X magazine while she was still steaming at 30 knots. The destroyer lost its stability and began rolling over at speed eventually capsizing but still continuing its forward momentum. She finally stopped all movement and for a while floated upside down with the length of her keel from stem to stern exposed. The screws were still turning while several of her crew clung precariously to the keel. All around the mortally wounded ship were men struggling to survive in a sea covered in a stinking thick mixture of fuel oil and debris. Some were killed in the initial blast; some drowned when the Kelly capsized or choked to death, their lungs full of oil or were killed when the Stukas returned to machine gun the struggling survivors.

Kelly finally tilted on an angle and slowly sank beneath the surface. Her brief but eventful life finally at an end. Perhaps those who watched her go possibly remembered lost shipmates, friends and a ship they had the honour and privilege to serve aboard. Survivors from both the Kelly and the Kashmir were clinging onto life amongst the wreckage of war. The situation looked hopeless. A few gave up and quietly slipped under the water, others fought the grim reaper with every ounce of their being. Captain Mountbatten and Lieutenant-Commander Beresford rescued many injured crew, swimming to someone in difficulty and getting him to the safety of a raft or piece of floating debris.

A ship was sighted heading towards them at full speed. Kipling came straight away, her defective steering finally repaired. The crew threw overboard to the men in the water anything that would float and lowered the scrambling nets over the sides. While they attempted to rescue the stricken sailors, the Germans persisted with their attacks on the men in the water and on the Kipling. Included among the rescued were Lord Mountbatten and his Lieutenant-Commander, Hugh Beresford. As Captain of the flotilla, Mountbatten took charge of the Kipling and the rescue operations. He immediately ordered the motorised life boat lowered into the water to assist in the rescue. As soon as the boat touched the water the Stukas attacked the Kipling again. The destroyer's 40,000 horsepower engine powering the destroyer forward in a surge of speed making it difficult to be hit. Unfortunately, the motor boat had not been released from the davit and this valuable rescue tool was being dragged under the sea bow first. Captain Mountbatten shouted out an order for someone to cut the after falls. Only First Lieutenant Beresford and the Kipling’s First Lieutenant John Bushe heard his order. Both immediately leapt to the after falls at the very moment the ship gathered speed. The heavy motorboat had sunk so deep in the water that the ship's speed wrenched the davit from its mooring taking the two officers with it and killing them both.

The slow and dangerous process of rescuing the helpless survivors under constant attack from the Luftwaffe continued but approximately three hours later, after having rescued some 279 officers and men, Kipling finally set a course for Alexandria 400 miles away. The Germans gave up trying to sink the ship allowing the Kipling to steam on through the night unmolested. At dawn, they ran out of fuel but Protector came out from Alexandria and replenished her fuel tanks. With great joy, the exhausted men saw the coast of Egypt and were soon entering the safety of Alexandria harbour. First Lieutenant Beresford’s body was washed up on the North African coast near Sollum a few days later and was buried there. He now rests in peace in the El Alamein Cemetery.

30th May 1941. The battle of Crete was one of the most bitter and exciting battles fought between German and Allied forces during the whole of the Second World War. The decisive action took place within five days and twice the outcome hung in the balance. By the third day, the number of German dead exceeded their losses in all other theatres since the outbreak of hostilities. The German parachutists were confined for supply and reinforcement to a single airstrip at Maleme where, from this one foothold, they managed to land over 8,000 men, who defeated an Allied army nearly five times as numerous. The defending forces fought with such ferocity, the Germans seriously considering breaking off the action and might have done so if the Allied Commander's nerve had not failed first. Although the German use of airborne troops, which was the first major airborne assault in history, was a major success, Hitler was so appalled by the enormous losses they suffered, he never ordered a large scale use of his airborne troops again. The successful use of airborne troops was a lesson not wasted on Allied Commanders and they were to use this new kind of warfare with varying degrees of success throughout the remainder of the war especially on D-Day 6 June.

The survivors of the two destroyers were given time to rest and recover from their horrific experience before being transferred to other ships to continue the war. Lord Mountbatten became Head of Combined Operation Command and helped plan the D-Day invasion. Later as Head of South East Asia Command he helped plan the defeat of the Japanese in Burma and Singapore. Some of his positions after the war included India’s last Viceroy and first Governor General and Aide de Camp to the Queen of England. He was murdered while out sailing with his family at his country home in County Sligo in Ireland by IRA terrorists in a bomb blast in 1979.

To summarise the story of Kelly is best done by using a quote from the forward to Kenneth Poolman’s excellent 1954 book ‘The Kelly’ which sadly, is out of print.

The Admiral the Earl Mountbatten of Burma, wrote; ‘The Kelly’ was sunk on May 23, 1941, in the Battle of Crete. No one left their posts when the end came. She went down with all her guns firing and with all her men at their action stations. We did not leave the Kelly, it was she who finally left us; but the spirit of her ship’s company lived on, as the spirit of all our other fighting ships did, and it was this spirit that contributed more than anything else to our ultimate victory at sea. This spirit still lives today in the Fleet.’

Internet References.

E-Boat S31.----------------------------------W.W.W. U-Boatnet

City of Flint. -----Kind permission------------- W.W.W. Moore-Mc Cormack.com

Oberleutnant Opdenhoff.---------------- W.W.W. U-Boatnet

Neville Chamberlain Speech.----------- W.W.W. doverpages.co.uk

Courageous Crew Losses. ----------------Fleetairarmarchives.net

Navy Controller comments.-------------- W.W.W.answers.com/topic/hms.Kelly

Death of Mountbatten.-------------------- Library.thinkquest.org.mountbatten

Reference Books.

Mountbatten Forward Quote. The Kelly-Kenneth Poolman. William Kimber Ltd, London. 1954. p V

Gang of Pirates Quote. Poolman. p 188.

Lord Beresford information. Poolman. p 150-151-203-213.

Mountbatten-Loss of Kelly. Michael J Kelly. Kind permission Naval Historical Society, NewSouth Wales, Australia.

Crete. Encyclopedia of Military History. R. E. Dupuy and T.N.Dupuy. Macdonald and Jane, London.1970.

Stuka Attack on Kelly. The Luftwaffe Diaries. Cajus Bekker. Corgi, 1969. P 255.

Kind Assistance.

Mackenzie Gregory.------- [email protected]

Paul Bevand. HMS Hood Association, United Kingdom.

Naval Historical Society of Australia [Inc] The Boatshed, Building 25, Garden Island, 2011, New South Wales, Australia.

Photographs.

The Kelly. Kenneth Poolman.William Kimber Ltd. London. 1954.

[Every effort was made to trace the copyright owner of the photographs and the author apologises for any unwitting case of copyright transgression.]

© Ken Wright 2005.

The survivors of the two destroyers were given time to rest and recover from their horrific experience before being transferred to other ships to continue the war. Lord Mountbatten became Head of Combined Operation Command and helped plan the D-Day invasion. Later as Head of South East Asia Command he helped plan the defeat of the Japanese in Burma and Singapore. Some of his positions after the war included India’s last Viceroy and first Governor General and Aide de Camp to the Queen of England. He was murdered while out sailing with his family at his country home in County Sligo in Ireland by IRA terrorists in a bomb blast in 1979.

To summarise the story of Kelly is best done by using a quote from the forward to Kenneth Poolman’s excellent 1954 book ‘The Kelly’ which sadly, is out of print.

The Admiral the Earl Mountbatten of Burma, wrote; ‘The Kelly’ was sunk on May 23, 1941, in the Battle of Crete. No one left their posts when the end came. She went down with all her guns firing and with all her men at their action stations. We did not leave the Kelly, it was she who finally left us; but the spirit of her ship’s company lived on, as the spirit of all our other fighting ships did, and it was this spirit that contributed more than anything else to our ultimate victory at sea. This spirit still lives today in the Fleet.’

Internet References.

E-Boat S31.----------------------------------W.W.W. U-Boatnet

City of Flint. -----Kind permission------------- W.W.W. Moore-Mc Cormack.com

Oberleutnant Opdenhoff.---------------- W.W.W. U-Boatnet

Neville Chamberlain Speech.----------- W.W.W. doverpages.co.uk

Courageous Crew Losses. ----------------Fleetairarmarchives.net

Navy Controller comments.-------------- W.W.W.answers.com/topic/hms.Kelly

Death of Mountbatten.-------------------- Library.thinkquest.org.mountbatten

Reference Books.

Mountbatten Forward Quote. The Kelly-Kenneth Poolman. William Kimber Ltd, London. 1954. p V

Gang of Pirates Quote. Poolman. p 188.

Lord Beresford information. Poolman. p 150-151-203-213.

Mountbatten-Loss of Kelly. Michael J Kelly. Kind permission Naval Historical Society, NewSouth Wales, Australia.

Crete. Encyclopedia of Military History. R. E. Dupuy and T.N.Dupuy. Macdonald and Jane, London.1970.

Stuka Attack on Kelly. The Luftwaffe Diaries. Cajus Bekker. Corgi, 1969. P 255.

Kind Assistance.

Mackenzie Gregory.------- [email protected]

Paul Bevand. HMS Hood Association, United Kingdom.

Naval Historical Society of Australia [Inc] The Boatshed, Building 25, Garden Island, 2011, New South Wales, Australia.

Photographs.

The Kelly. Kenneth Poolman.William Kimber Ltd. London. 1954.

[Every effort was made to trace the copyright owner of the photographs and the author apologises for any unwitting case of copyright transgression.]

© Ken Wright 2005.