KRANJI WAR CEMETERY

Singapore

Location Information

Kranji War Cemetery is 22 kilometres north of the city of Singapore, on the north side of Singapore Island overlooking the Straits of Johore. It is located just to the West of the Singapore-Johore road (Bukit Timah Expressway) on Woodlands Road, just to the south of the crossroads with Turf Club Avenue and Kranji Road. There is a short approach road from the main road.

The Cemetery is known locally as Kranji Memorial and one must be sure of the address before boarding a taxi as most taxi drivers do not know the Cemetery. There are also bus stops on the main road facing the Cemetery. The Kranji MRT (train) terminal is a short distance from the Cemetery, approximately 10 to 15 minutes away by foot. A previous visitor has advised us that a small map of the route can be obtained from the MRT ticket office.

Visiting Information

Kranji War Cemetery is open every day 07:00-18:30. The cemetery is constructed on a hill with the means of access being via three flights of steps, rising over four metres from the road level, which makes wheelchair access to this site impossible.

Historical Information

Before 1939, the Kranji area was a military camp and at the time of the Japanese invasion of Malaya, it was the site of a large ammunition magazine. On 8 February 1942, the Japanese crossed the Johore Straits in strength, landing at the mouth of the Kranji River within two miles of the place where the war cemetery now stands. On the evening of 9 February, they launched an attack between the river and the causeway. During the next few days fierce fighting ensued, in many cases hand to hand, until their greatly superior numbers and air strength necessitated a withdrawal.

After the fall of the island, the Japanese established a prisoner of war camp at Kranji and eventually a hospital was organised nearby at Woodlands.

After the reoccupation of Singapore, the small cemetery started by the prisoners at Kranji was developed into a permanent war cemetery by the Army Graves Service when it became evident that a larger cemetery at Changi could not remain undisturbed. Changi had been the site of the main prisoner of war camp in Singapore and a large hospital had been set up there by the Australian Infantry Force. In 1946, the graves were moved from Changi to Kranji, as were those from the Buona Vista prisoner of war camp. Many other graves from all parts of the island were transferred to Kranji together with all Second World War graves from Saigon Military Cemetery in French Indo-China (now Vietnam), another site where permanent maintenance could not be assured.

The Commission later brought in graves of both World Wars from Bidadari Christian Cemetery, Singapore, where again permanent maintenance was not possible.

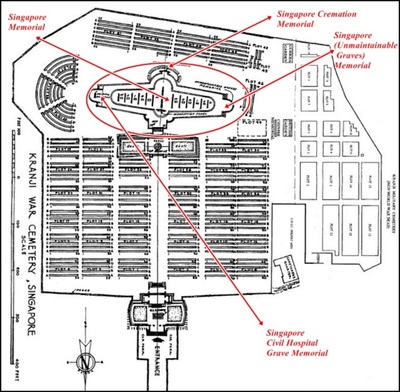

There are now 4,461 Commonwealth casualties of the Second World War buried or commemorated at KRANJI WAR CEMETERY. More than 850 of the burials are unidentified. The Chinese Memorial in Plot 44 marks a collective grave for 69 Chinese servicemen, all members of the Commonwealth forces, who were killed by the Japanese during the occupation in February 1942.

First World War burials and commemorations number 64, including special memorials to three casualties known to have been buried in civil cemeteries in Saigon and Singapore, but whose graves could not be located.

Within Kranji War Cemetery stands the SINGAPORE MEMORIAL, bearing the names of over 24,000 casualties of the Commonwealth land and air forces who have no known grave. Many of these have no known date of death and are accorded within our records the date or period from when they were known to be missing or captured. The land forces commemorated by the memorial died during the campaigns in Malaya and Indonesia or in subsequent captivity, many of them during the construction of the Burma-Thailand railway, or at sea while being transported into imprisonment elsewhere. The memorial also commemorates airmen who died during operations over the whole of southern and eastern Asia and the surrounding seas and oceans.

The SINGAPORE (UNMAINTAINABLE GRAVES) MEMORIAL, which stands at the western end of the Singapore Memorial, commemorates more than 250 casualties who died in campaigns in Singapore and Malaya, whose known graves in civil cemeteries could not be assured maintenance and on religious grounds could not be moved to a war cemetery.

The SINGAPORE CREMATION MEMORIAL, which stands immediately behind the Singapore Memorial, commemorates almost 800 casualties, mostly of the Indian forces, whose remains were cremated in accordance with their religious beliefs.

The SINGAPORE CIVIL HOSPITAL GRAVE MEMORIAL stands at the eastern end of the Singapore Memorial. During the last hours of the Battle of Singapore, wounded civilians and servicemen taken prisoner by the Japanese were brought to the hospital in their hundreds. The number of fatalities was such that burial in the normal manner was impossible. Before the war, an emergency water tank had been dug in the grounds of the hospital and this was used as a grave for more than 400 civilians and Commonwealth servicemen.

After the war, it was decided that as individual identification of the dead would be impossible, the grave should be left undisturbed. The grave was suitably enclosed, consecrated by the Bishop of Singapore, and a cross in memory of all of those buried there was erected over it by the military authorities. The 107 Commonwealth casualties buried in the grave are commemorated on the Singapore Civil Hospital Grave Memorial.

Kranji War Cemetery and the Singapore Memorial were designed by Colin St Clair Oakes.

Adjoining Kranji War Cemetery is KRANJI MILITARY CEMETERY, a substantial non-world war site of 1,422 burials, created in 1975 when it was found necessary to remove the graves of servicemen and their families from Pasir Panjang and Ulu Pandan cemeteries.

Kranji War Cemetery is 22 kilometres north of the city of Singapore, on the north side of Singapore Island overlooking the Straits of Johore. It is located just to the West of the Singapore-Johore road (Bukit Timah Expressway) on Woodlands Road, just to the south of the crossroads with Turf Club Avenue and Kranji Road. There is a short approach road from the main road.

The Cemetery is known locally as Kranji Memorial and one must be sure of the address before boarding a taxi as most taxi drivers do not know the Cemetery. There are also bus stops on the main road facing the Cemetery. The Kranji MRT (train) terminal is a short distance from the Cemetery, approximately 10 to 15 minutes away by foot. A previous visitor has advised us that a small map of the route can be obtained from the MRT ticket office.

Visiting Information

Kranji War Cemetery is open every day 07:00-18:30. The cemetery is constructed on a hill with the means of access being via three flights of steps, rising over four metres from the road level, which makes wheelchair access to this site impossible.

Historical Information

Before 1939, the Kranji area was a military camp and at the time of the Japanese invasion of Malaya, it was the site of a large ammunition magazine. On 8 February 1942, the Japanese crossed the Johore Straits in strength, landing at the mouth of the Kranji River within two miles of the place where the war cemetery now stands. On the evening of 9 February, they launched an attack between the river and the causeway. During the next few days fierce fighting ensued, in many cases hand to hand, until their greatly superior numbers and air strength necessitated a withdrawal.

After the fall of the island, the Japanese established a prisoner of war camp at Kranji and eventually a hospital was organised nearby at Woodlands.

After the reoccupation of Singapore, the small cemetery started by the prisoners at Kranji was developed into a permanent war cemetery by the Army Graves Service when it became evident that a larger cemetery at Changi could not remain undisturbed. Changi had been the site of the main prisoner of war camp in Singapore and a large hospital had been set up there by the Australian Infantry Force. In 1946, the graves were moved from Changi to Kranji, as were those from the Buona Vista prisoner of war camp. Many other graves from all parts of the island were transferred to Kranji together with all Second World War graves from Saigon Military Cemetery in French Indo-China (now Vietnam), another site where permanent maintenance could not be assured.

The Commission later brought in graves of both World Wars from Bidadari Christian Cemetery, Singapore, where again permanent maintenance was not possible.

There are now 4,461 Commonwealth casualties of the Second World War buried or commemorated at KRANJI WAR CEMETERY. More than 850 of the burials are unidentified. The Chinese Memorial in Plot 44 marks a collective grave for 69 Chinese servicemen, all members of the Commonwealth forces, who were killed by the Japanese during the occupation in February 1942.

First World War burials and commemorations number 64, including special memorials to three casualties known to have been buried in civil cemeteries in Saigon and Singapore, but whose graves could not be located.

Within Kranji War Cemetery stands the SINGAPORE MEMORIAL, bearing the names of over 24,000 casualties of the Commonwealth land and air forces who have no known grave. Many of these have no known date of death and are accorded within our records the date or period from when they were known to be missing or captured. The land forces commemorated by the memorial died during the campaigns in Malaya and Indonesia or in subsequent captivity, many of them during the construction of the Burma-Thailand railway, or at sea while being transported into imprisonment elsewhere. The memorial also commemorates airmen who died during operations over the whole of southern and eastern Asia and the surrounding seas and oceans.

The SINGAPORE (UNMAINTAINABLE GRAVES) MEMORIAL, which stands at the western end of the Singapore Memorial, commemorates more than 250 casualties who died in campaigns in Singapore and Malaya, whose known graves in civil cemeteries could not be assured maintenance and on religious grounds could not be moved to a war cemetery.

The SINGAPORE CREMATION MEMORIAL, which stands immediately behind the Singapore Memorial, commemorates almost 800 casualties, mostly of the Indian forces, whose remains were cremated in accordance with their religious beliefs.

The SINGAPORE CIVIL HOSPITAL GRAVE MEMORIAL stands at the eastern end of the Singapore Memorial. During the last hours of the Battle of Singapore, wounded civilians and servicemen taken prisoner by the Japanese were brought to the hospital in their hundreds. The number of fatalities was such that burial in the normal manner was impossible. Before the war, an emergency water tank had been dug in the grounds of the hospital and this was used as a grave for more than 400 civilians and Commonwealth servicemen.

After the war, it was decided that as individual identification of the dead would be impossible, the grave should be left undisturbed. The grave was suitably enclosed, consecrated by the Bishop of Singapore, and a cross in memory of all of those buried there was erected over it by the military authorities. The 107 Commonwealth casualties buried in the grave are commemorated on the Singapore Civil Hospital Grave Memorial.

Kranji War Cemetery and the Singapore Memorial were designed by Colin St Clair Oakes.

Adjoining Kranji War Cemetery is KRANJI MILITARY CEMETERY, a substantial non-world war site of 1,422 burials, created in 1975 when it was found necessary to remove the graves of servicemen and their families from Pasir Panjang and Ulu Pandan cemeteries.

4746298, Lance Bombardier

Bernard Bradley

85 Anti-Tank Regt.Royal Artillery

31st July 1945, aged 25.

Plot 16. E. 6.

Son of William and Kathleen Bradley, of Worplesdon, Surrey.

Bernard and his brother Harry survived evacuation from Dunkirk and shortly after some leave, were drafted to Singapore. Both became POWs on the fall of Singapore. Harry survived and continued to serve in the Royal Artillery until he was 55, finishing as Sergeant Major.

Photo Courtesy of Peter Magnall, Cousin of Bernard Bradley

Bernard Bradley

85 Anti-Tank Regt.Royal Artillery

31st July 1945, aged 25.

Plot 16. E. 6.

Son of William and Kathleen Bradley, of Worplesdon, Surrey.

Bernard and his brother Harry survived evacuation from Dunkirk and shortly after some leave, were drafted to Singapore. Both became POWs on the fall of Singapore. Harry survived and continued to serve in the Royal Artillery until he was 55, finishing as Sergeant Major.

Photo Courtesy of Peter Magnall, Cousin of Bernard Bradley

809817 Sergeant

Thomas John French

Royal Artillery 420 Battery

148 (The Bedfordshire Yeomanry) Field Regiment

3rd February 1942 aged 26.

Son of Thomas James French and Ethel Jane French of Camelford, Cornwall

Extract taken from the Cornish and Devon Post dated 07/03/1942.

Sergeant Thomas John French aged 26, the eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. T. French, of Lane End, Camelford, has died of wounds received whilst on active service in the Far East. In 1931 at the early age of 15, he enlisted in the Royal Artillery as a trumpeter. Showing signs of great promise, he soon won his 3rd and 2nd class certificates and in 1933 was drafted to Egypt where he served for six years and four months. Whilst in Egypt and in is 17th year he won his first class certificate. Returning to England in 1939 he was promoted to sergeant. Last year he went to the Far East where he died on the 3rd of February. Much sympathy is felt with his parents and the other members of his family in their loss. Three Camelford lads representative of the Navy, Army and Air Force have now made the Supreme Sacrifice for their country.

Thomas John French

Royal Artillery 420 Battery

148 (The Bedfordshire Yeomanry) Field Regiment

3rd February 1942 aged 26.

Son of Thomas James French and Ethel Jane French of Camelford, Cornwall

Extract taken from the Cornish and Devon Post dated 07/03/1942.

Sergeant Thomas John French aged 26, the eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. T. French, of Lane End, Camelford, has died of wounds received whilst on active service in the Far East. In 1931 at the early age of 15, he enlisted in the Royal Artillery as a trumpeter. Showing signs of great promise, he soon won his 3rd and 2nd class certificates and in 1933 was drafted to Egypt where he served for six years and four months. Whilst in Egypt and in is 17th year he won his first class certificate. Returning to England in 1939 he was promoted to sergeant. Last year he went to the Far East where he died on the 3rd of February. Much sympathy is felt with his parents and the other members of his family in their loss. Three Camelford lads representative of the Navy, Army and Air Force have now made the Supreme Sacrifice for their country.

NX50220 Private

James Bryce MacLaren Pryde

2/18th Bn. Australian Infantry

27th January 1942, aged 24.

Sp.Mem. 6. D. 2.

James Bryce MacLaren Pryde was born in Edinburgh, Scotland 20/1/1918 and emigrated to McMahons Point, New South Wales, Australia with his parents William and Jean Law Keith Pryde in 1937.

James enlisted in the Australian Army at Paddington in the Wahroonga area of Sydney. His service number was NX50220 and he gave his father as next of kin.

James saw fighting in Singapore and died in Changi hospital on 27/1/1942. James is buried/commemorated on Panel 42 at Kranji Military Cemetery.

Son of Scotland buried in a foreign field - remembered by his family

James Bryce MacLaren Pryde

2/18th Bn. Australian Infantry

27th January 1942, aged 24.

Sp.Mem. 6. D. 2.

James Bryce MacLaren Pryde was born in Edinburgh, Scotland 20/1/1918 and emigrated to McMahons Point, New South Wales, Australia with his parents William and Jean Law Keith Pryde in 1937.

James enlisted in the Australian Army at Paddington in the Wahroonga area of Sydney. His service number was NX50220 and he gave his father as next of kin.

James saw fighting in Singapore and died in Changi hospital on 27/1/1942. James is buried/commemorated on Panel 42 at Kranji Military Cemetery.

Son of Scotland buried in a foreign field - remembered by his family

ESCAPE AND DIE

(All pictures and text by Ken Wright)

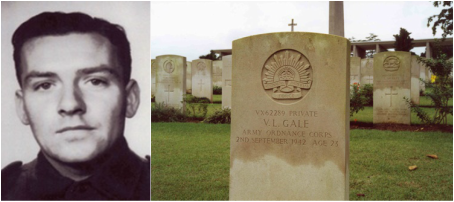

Rodney Breavington and Victor Gale

Before the fall of Singapore, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill insisted that, ‘There must be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs. Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and the British Army is at stake’.

Desperately short of ammunition, food, water and other essential supplies, the defending troops fought valiantly but with mounting casualties, both civilian and military, the Allied Commander, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival was forced to face the reality of the military situation and disobeyed his orders. He accepted Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s ultimatum and signed an unconditional surrender of all allied forces in Singapore on 15 February 1942. It was celebrated as magnificent victory by the Imperial Japanese Army and it was the end of British colonial power in the Far East. The surrender was to have serious implications for the captured allied soldiers and the people of Singapore over the next three and a half years of Japanese military occupation.

In the early stages of the war, the Japanese found themselves burdened with hundreds of thousands of prisoners dotted all over South East Asia. For them, the problem of having so many Prisoners of War became a major concern. It was not until the arrival of Major-General Shimpei Fukuye and a large administration staff in Singapore that the POW situation on the island became more organized. As the Japanese did not recognize the right of any POW to escape, an order went down to most commandants of prison camps throughout the occupied territories to demand each prisoner sign the following document [order no 7 ] promising not to escape.

I, the undersigned, hereby solemnly swear on my honour, that I will not, under any circumstances, attempt to escape.

This document was contrary to the rules of war as laid down in the Geneva Convention which permitted American, Australian and British prisoners of war the right to escape. When the document was issued to the senior officers in Changi prison on 31 August, it was only natural that all Allied Commanders and other ranks refused to sign. As the Japanese were not signatories to the Geneva Convention, they felt they could take whatever action deemed necessary to maintain control and the Allied Commanders refusal to sign could only lead to confrontation. Two days passed with no sign of what Japanese command was going to do. Then on the morning of 2 September 1942, all POWs were ordered to take their personal kit, cooking utensils, stores and move to Selarang Barracks close by to Changi. Any POW not in Selerang Barracks by 6pm would be shot.

Selarang Barracks had been home to a Battalion of Gordon Highlanders since its completion in 1938 but during the Japanese occupation from 1942-1945; the barracks were used as a POW camp housing mainly Australians. Approximately 15,400 men were crowded into a barracks designed to house only 1,200. With only two water taps, totally inadequate latrine facilities, a blazing hot tropical sun and food rations cut, the ‘wait and see what happens next’ period began. To further intimidate the allied soldiers to sign, four prisoners were taken to Changi beach that same day and executed in front of a select group of Senior Allied Commanders. Why were these four singled out for execution? They were escapees.

Corporal Rodney Breavington [38] and Private Victor Gale [23] were both members of the Royal Australian Ordnance Corps. They had become prisoners of war on the evening of the 15 of February 1942 when surrender orders were received. Private T Thwaites [also a member of the same unit] was with Corporal Breavington a few days before the surrender. He wrote after the war;

‘It was getting late in the afternoon when we got to our position and all the rest of the day and during the night, Corporal Breavington walked up and down like a father making sure we were ok. About 6pm on the 15 February, orders came through to lay down our arms. The corporal called for a couple of volunteers. A mate and I volunteered and his orders were to go around and break every bottle of grog [alcohol] we could find as he was concerned about his men. It would be bad enough when the Japs came but he didn’t want his men pissed as that would make things twice as bad. About 10pm we were told to proceed to the tennis court and his last order as corporal was for all of us to take the bolts out of our rifles and throw them away’

Desperately short of ammunition, food, water and other essential supplies, the defending troops fought valiantly but with mounting casualties, both civilian and military, the Allied Commander, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival was forced to face the reality of the military situation and disobeyed his orders. He accepted Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s ultimatum and signed an unconditional surrender of all allied forces in Singapore on 15 February 1942. It was celebrated as magnificent victory by the Imperial Japanese Army and it was the end of British colonial power in the Far East. The surrender was to have serious implications for the captured allied soldiers and the people of Singapore over the next three and a half years of Japanese military occupation.

In the early stages of the war, the Japanese found themselves burdened with hundreds of thousands of prisoners dotted all over South East Asia. For them, the problem of having so many Prisoners of War became a major concern. It was not until the arrival of Major-General Shimpei Fukuye and a large administration staff in Singapore that the POW situation on the island became more organized. As the Japanese did not recognize the right of any POW to escape, an order went down to most commandants of prison camps throughout the occupied territories to demand each prisoner sign the following document [order no 7 ] promising not to escape.

I, the undersigned, hereby solemnly swear on my honour, that I will not, under any circumstances, attempt to escape.

This document was contrary to the rules of war as laid down in the Geneva Convention which permitted American, Australian and British prisoners of war the right to escape. When the document was issued to the senior officers in Changi prison on 31 August, it was only natural that all Allied Commanders and other ranks refused to sign. As the Japanese were not signatories to the Geneva Convention, they felt they could take whatever action deemed necessary to maintain control and the Allied Commanders refusal to sign could only lead to confrontation. Two days passed with no sign of what Japanese command was going to do. Then on the morning of 2 September 1942, all POWs were ordered to take their personal kit, cooking utensils, stores and move to Selarang Barracks close by to Changi. Any POW not in Selerang Barracks by 6pm would be shot.

Selarang Barracks had been home to a Battalion of Gordon Highlanders since its completion in 1938 but during the Japanese occupation from 1942-1945; the barracks were used as a POW camp housing mainly Australians. Approximately 15,400 men were crowded into a barracks designed to house only 1,200. With only two water taps, totally inadequate latrine facilities, a blazing hot tropical sun and food rations cut, the ‘wait and see what happens next’ period began. To further intimidate the allied soldiers to sign, four prisoners were taken to Changi beach that same day and executed in front of a select group of Senior Allied Commanders. Why were these four singled out for execution? They were escapees.

Corporal Rodney Breavington [38] and Private Victor Gale [23] were both members of the Royal Australian Ordnance Corps. They had become prisoners of war on the evening of the 15 of February 1942 when surrender orders were received. Private T Thwaites [also a member of the same unit] was with Corporal Breavington a few days before the surrender. He wrote after the war;

‘It was getting late in the afternoon when we got to our position and all the rest of the day and during the night, Corporal Breavington walked up and down like a father making sure we were ok. About 6pm on the 15 February, orders came through to lay down our arms. The corporal called for a couple of volunteers. A mate and I volunteered and his orders were to go around and break every bottle of grog [alcohol] we could find as he was concerned about his men. It would be bad enough when the Japs came but he didn’t want his men pissed as that would make things twice as bad. About 10pm we were told to proceed to the tennis court and his last order as corporal was for all of us to take the bolts out of our rifles and throw them away’

Breavington and his men were sent to Selarang Barracks then to a camp at Bukit Timar. At nearby Bukit Batok, one of the fiercest battles for Singapore was fought and it was there they were forced to work on the Syonan Chureito, a monument to honour the Japanese war dead. This monument was built by 500 prisoners of war over a six month period. The prisoners had to remove the top of a hill and erect a 40- foot wooden pylon topped by a brass cone. The pylon was set in a stepped concrete base. At the rear of the Japanese monument, permission was given for the POWs to build a small monument to honour their own dead. It was represented by a small 10- foot cross. Both were destroyed by the Japanese before the British forces returned to Singapore in 1945.

There is little information available about Breavington and Gales attempted escape or how they got to the coast from the Bukit Timar P.O.W Camp. It is known they managed to ‘liberate’ a small boat on or around the 12 May and row [or drift] approximately 200 miles possibly south-east towards the west coast of Borneo. They may have beached on a small island looking for food and water and it is believed that this is where the natives betrayed them to the local Japanese garrison. They were recaptured and eventually sent to Changi prison.

Almost three years later, between the 21 and 27 August, 1945, signed statements were made before Captain J.M.Lewis, General List, [Legal] Headquarters, Malaya Command, by the remaining Senior Commanders present at the execution. Their statements differ as to the events on that fateful day, but by combining their version of the events as each individual saw it, a picture emerges of a chilling ruthlessness on the part of the Japanese and bravery by the condemned men that impressed the Commanders that were compelled to watch the execution.

At 11am on 2 September, 1942, the day all POWs were ordered to move from Changi to Selerang, a written demand was delivered by a pro-Japanese Indian prisoner from the Japanese authorities to Allied General Headquarters in Changi that four prisoners, Breavington, Gale, Waters and Fletcher be handed over and placed in a waiting truck.

The Duty Officer, Major Magee, using an Indian Army Officer as an interpreter explained two were in the camp hospital and two were in different sectors of the camp. The driver left to pick up the men who were eventually taken to Curran camp, the Japanese punishment area. The Commander of the allied prisoners, Colonel E.B.Holmes, was aware of the Imperial Japanese Army’s intention to execute escapees and drew up a formal plea for clemency.

‘I have the honour to submit this earnest appeal for your reconsideration of the infliction of the supreme penalty on four prisoners of war who have been apprehended attempting to escape from this camp.’

‘I am aware that it has been made perfectly clear by you that any such attempts will incur the penalty of death and furthermore there is no misapprehension on the part of the prisoners themselves that this is so.’

‘I will however, take immediate steps again to impress on all ranks in this camp, the inevitable outcome of any attempt to escape and beg that in the present instance, you will exercise your clemency by the infliction of a less severe punishment than that of execution.’

The plea was addressed to Major General Fukuye and it was delivered to Japanese Headquarters. The Japanese Duty Officer, who understood some English, read it, became angry, tore up the petition and threw it in the face of the Captain who had delivered it.

There is little information available about Breavington and Gales attempted escape or how they got to the coast from the Bukit Timar P.O.W Camp. It is known they managed to ‘liberate’ a small boat on or around the 12 May and row [or drift] approximately 200 miles possibly south-east towards the west coast of Borneo. They may have beached on a small island looking for food and water and it is believed that this is where the natives betrayed them to the local Japanese garrison. They were recaptured and eventually sent to Changi prison.

Almost three years later, between the 21 and 27 August, 1945, signed statements were made before Captain J.M.Lewis, General List, [Legal] Headquarters, Malaya Command, by the remaining Senior Commanders present at the execution. Their statements differ as to the events on that fateful day, but by combining their version of the events as each individual saw it, a picture emerges of a chilling ruthlessness on the part of the Japanese and bravery by the condemned men that impressed the Commanders that were compelled to watch the execution.

At 11am on 2 September, 1942, the day all POWs were ordered to move from Changi to Selerang, a written demand was delivered by a pro-Japanese Indian prisoner from the Japanese authorities to Allied General Headquarters in Changi that four prisoners, Breavington, Gale, Waters and Fletcher be handed over and placed in a waiting truck.

The Duty Officer, Major Magee, using an Indian Army Officer as an interpreter explained two were in the camp hospital and two were in different sectors of the camp. The driver left to pick up the men who were eventually taken to Curran camp, the Japanese punishment area. The Commander of the allied prisoners, Colonel E.B.Holmes, was aware of the Imperial Japanese Army’s intention to execute escapees and drew up a formal plea for clemency.

‘I have the honour to submit this earnest appeal for your reconsideration of the infliction of the supreme penalty on four prisoners of war who have been apprehended attempting to escape from this camp.’

‘I am aware that it has been made perfectly clear by you that any such attempts will incur the penalty of death and furthermore there is no misapprehension on the part of the prisoners themselves that this is so.’

‘I will however, take immediate steps again to impress on all ranks in this camp, the inevitable outcome of any attempt to escape and beg that in the present instance, you will exercise your clemency by the infliction of a less severe punishment than that of execution.’

The plea was addressed to Major General Fukuye and it was delivered to Japanese Headquarters. The Japanese Duty Officer, who understood some English, read it, became angry, tore up the petition and threw it in the face of the Captain who had delivered it.

Changi Beach

At approximately 11.30 am, that same morning, the Senior Commanders including two Chaplains were ordered to assemble at a specified rendezvous point and driven by truck to Changi beach. A party of Japanese Officers were already there, laughing and smoking, including Lieutenant Okasaki, staff officer to Major General Fukuke and a Japanese interpreter. Some time later, two of the victims arrived; Breavington was still very ill from malaria and berri-berri and had to be assisted by Fletcher. Both were still wearing pyjamas as they had just been removed from the camp hospital. Waters and Gale arrived a short time later. Australian documents say little about Fletcher [21] and Waters [23] as both belonged to the British Army and had attempted to escape quite independently from the two Australians. The firing party, comprising three Sikhs and a renegade Indian Officer, Lieutenant Rama [or Captain Rana] also arrived. The time was approximately 12midday. The four men were paraded in front of Lieutenant Okasaki and an interpreter. They were told they were guilty of attempting to escape which was against Imperial Japanese Army orders and they were to be shot. They were given five minutes to prepare themselves.

Corporal Breavington pleaded with the Japanese Officer to let Private Gale go as he, the senior officer, had ordered Gale to escape .He also asked for the two British soldiers to be spared as well according to one witness. Certainly he tried to save Gale by placing all the responsibility on his shoulders alone and asked that only he be shot. His request was refused. An Anglican Chaplain prayed with them, gave them absolution, and took some last instructions. Corporal Breavington asked for a New Testament and read a short passage. The chaplain then returned to the group of Senior Commanders. Private Fletcher is reported to have joked, ‘I only hope they are good shots, sir.’ The prisoners were then led to a spot on the beach with their backs to the sea. An offer of a blindfold was made by Lieutenant Okasaki but scornfully rejected. The firing party took up positions in front of the condemned men, assumed a kneeling position, one opposite each target. The Senior Commanders saluted the prisoners who returned the salute, and then the order to fire was given by Lieutenant Okasaki. All four victims fell to the ground. At this point the witnesses were unsure if all of the victims were dead. Only Breavington was reported to have cried out, ‘For God’s sake finish me off. You have only shot me in the arm ‘or words to that effect. The fact that he was still alive may have caused some panic amongst the firing party because of their inaccurate rifle fire as many more shots were fired at the bodies on the ground until all movement had ceased. One officer present estimated a total of 16 shots were fired at the victims. The Indians then produced picks and shovels and buried the executed men in shallow graves.

Lieutenant Okasaki, through the interpreter, addressed the Allied Commanders. ‘You have witnessed four men put to death. They tried to escape against Japanese orders. It is impossible for anyone to escape as the great Japanese own all countries in the south and anyone escaping from here must be caught. They will be brought back and put to death. You are responsible for the men under your command and you will again tell them not to go outside the wire as they will be put to death as you have just seen. We do not like to put them to death. You have not signed the paper saying you will not escape which is an admission that you intend to escape.’

Lt-Col Gallagher informed Lt Okasaki that they had no idea of escaping and that it was foolish to do so and that all the men had been so informed. The witnesses were then returned to the rendezvous point by truck. The senior officers did eventually order the men under their command to sign the document but with the clarification that because it was being signed under duress, it was not legally binding.

In a quote from a letter written to Corporal Breavington’s wife Margaret the day after the execution, his commanding officer, Lieutenant -Colonel Fredrick [Black Jack] Gallagher said; ‘Your husband’s calmness and bravery was outstanding. He was to me the bravest man I have ever seen.’ [Japanese authorities did not allow any out going mail. It was only after the Japanese surrender in 1945 that the letter was able to be sent] Breavington was certainly a brave and exceptional man but Gale, Waters and Fletcher were also brave men and died with honour.

Who was Corporal Rodney Breavington ? A former member of the New Zealand Army, Breavington came to Australia and settled in the Victorian state capital of Melbourne. He joined the Victoria Police in 1928 and after a two month training period, was sent to the Police HQ in Melbourne. For three years he worked as a junior constable doing street work until August 1931 when he was posted to the Northcote Police station [a suburb of Melbourne] and remained there for the rest of his police career. Promoted to Senior Constable after five years with two years in plain clothes and a conduct record that lists two official commendations for ‘vigilance and diligence’ and his annual appraisal was listed as ‘well conducted and nothing negative’. Not even a disciplinary charge or reprimand. Breavingtons record was immaculate. He remained at the Northcote Station until resigning on 7 December 1941 to join the 2nd Australian Imperial Forces. After initial training he was assigned to the Royal Australian Ordinance Corps and sent to Singapore with the rank of Corporal. Three weeks later when Singapore surrendered, he became a prisoner of war.

The RAOC has accepted him as their Corps hero of WW2 and established the Breavington and Gale Memorial Gardens at the base in Bandiana in New South Wales. The military establishment at Enoggera near Brisbane, Queensland, has a Breavington canteen and mess and in his home town, there is a park named after him. His name is mentioned with honour at the local Returned Services League clubs. Both Breavington and Gale were posthumously awarded the 1939/45 Star, the Pacific Star, the British War Medal and the Australian War Medal.

When Japan surrendered in 1945, Singapore was reoccupied by the Allies and vengeance was swift. Major-General Fukuye was taken to Changi beach and executed without trial on the 16 August by Australian troops for his part in the execution of the four allied POWs and for the thousands of Chinese civilians murdered between February 15, 1942 and July 25, 1945 on suspicion of being anti-Japanese. The Tanah Merah Beach, located at the end of the present Changi Airport runway, was a one of the most heavily used killing grounds where well over a thousand Chinese men and youths were executed.

Lieutenant Okasaki was put on trial, found guilty of war crimes and executed by a firing squad at the precise spot as were the four POWs he had so callously ordered shot back on September 2. At least he died instantly with the merciful swiftness of a volley of accurate rifle fire which is more than could be said for his four unfortunate victims of Japanese barbarism.

The soldiers and civilians of all nations, who had the misfortune to fall into Japanese hands during WW2, suffered so much. Many were murdered, thousands died from sheer neglect. Many who returned home never recovered from their experiences. What the Japanese did to those under their military control was appalling. The bodies of Breavington, Gale, Fletcher and Waters were exhumed by Australian and British burial parties on 22 September 1945. The two Australians now rest in peace in the Kranji War Memorial Cemetery in Singapore.

References.

History of Changi. H. A. Probert. Published by Changi State Prison.1965.

Prisoners of the Japanese. Burgess and Breddon. Time Life 1988.

Northcote Police Station Archives. Melbourne, Victoria. Australia.

Northcote’s Bravest Son. By R. Harcourt. Return Services League Publication 1999.

The Deaths of Breavington, Gale, Waters, Fletcher. By R. Settle

Personal Memories. T. Thwaites Ex RAOC member.

National Archives of Australia-Canberra, ACT,Australia.

[C] KenWright. 2004.

Corporal Breavington pleaded with the Japanese Officer to let Private Gale go as he, the senior officer, had ordered Gale to escape .He also asked for the two British soldiers to be spared as well according to one witness. Certainly he tried to save Gale by placing all the responsibility on his shoulders alone and asked that only he be shot. His request was refused. An Anglican Chaplain prayed with them, gave them absolution, and took some last instructions. Corporal Breavington asked for a New Testament and read a short passage. The chaplain then returned to the group of Senior Commanders. Private Fletcher is reported to have joked, ‘I only hope they are good shots, sir.’ The prisoners were then led to a spot on the beach with their backs to the sea. An offer of a blindfold was made by Lieutenant Okasaki but scornfully rejected. The firing party took up positions in front of the condemned men, assumed a kneeling position, one opposite each target. The Senior Commanders saluted the prisoners who returned the salute, and then the order to fire was given by Lieutenant Okasaki. All four victims fell to the ground. At this point the witnesses were unsure if all of the victims were dead. Only Breavington was reported to have cried out, ‘For God’s sake finish me off. You have only shot me in the arm ‘or words to that effect. The fact that he was still alive may have caused some panic amongst the firing party because of their inaccurate rifle fire as many more shots were fired at the bodies on the ground until all movement had ceased. One officer present estimated a total of 16 shots were fired at the victims. The Indians then produced picks and shovels and buried the executed men in shallow graves.

Lieutenant Okasaki, through the interpreter, addressed the Allied Commanders. ‘You have witnessed four men put to death. They tried to escape against Japanese orders. It is impossible for anyone to escape as the great Japanese own all countries in the south and anyone escaping from here must be caught. They will be brought back and put to death. You are responsible for the men under your command and you will again tell them not to go outside the wire as they will be put to death as you have just seen. We do not like to put them to death. You have not signed the paper saying you will not escape which is an admission that you intend to escape.’

Lt-Col Gallagher informed Lt Okasaki that they had no idea of escaping and that it was foolish to do so and that all the men had been so informed. The witnesses were then returned to the rendezvous point by truck. The senior officers did eventually order the men under their command to sign the document but with the clarification that because it was being signed under duress, it was not legally binding.

In a quote from a letter written to Corporal Breavington’s wife Margaret the day after the execution, his commanding officer, Lieutenant -Colonel Fredrick [Black Jack] Gallagher said; ‘Your husband’s calmness and bravery was outstanding. He was to me the bravest man I have ever seen.’ [Japanese authorities did not allow any out going mail. It was only after the Japanese surrender in 1945 that the letter was able to be sent] Breavington was certainly a brave and exceptional man but Gale, Waters and Fletcher were also brave men and died with honour.

Who was Corporal Rodney Breavington ? A former member of the New Zealand Army, Breavington came to Australia and settled in the Victorian state capital of Melbourne. He joined the Victoria Police in 1928 and after a two month training period, was sent to the Police HQ in Melbourne. For three years he worked as a junior constable doing street work until August 1931 when he was posted to the Northcote Police station [a suburb of Melbourne] and remained there for the rest of his police career. Promoted to Senior Constable after five years with two years in plain clothes and a conduct record that lists two official commendations for ‘vigilance and diligence’ and his annual appraisal was listed as ‘well conducted and nothing negative’. Not even a disciplinary charge or reprimand. Breavingtons record was immaculate. He remained at the Northcote Station until resigning on 7 December 1941 to join the 2nd Australian Imperial Forces. After initial training he was assigned to the Royal Australian Ordinance Corps and sent to Singapore with the rank of Corporal. Three weeks later when Singapore surrendered, he became a prisoner of war.

The RAOC has accepted him as their Corps hero of WW2 and established the Breavington and Gale Memorial Gardens at the base in Bandiana in New South Wales. The military establishment at Enoggera near Brisbane, Queensland, has a Breavington canteen and mess and in his home town, there is a park named after him. His name is mentioned with honour at the local Returned Services League clubs. Both Breavington and Gale were posthumously awarded the 1939/45 Star, the Pacific Star, the British War Medal and the Australian War Medal.

When Japan surrendered in 1945, Singapore was reoccupied by the Allies and vengeance was swift. Major-General Fukuye was taken to Changi beach and executed without trial on the 16 August by Australian troops for his part in the execution of the four allied POWs and for the thousands of Chinese civilians murdered between February 15, 1942 and July 25, 1945 on suspicion of being anti-Japanese. The Tanah Merah Beach, located at the end of the present Changi Airport runway, was a one of the most heavily used killing grounds where well over a thousand Chinese men and youths were executed.

Lieutenant Okasaki was put on trial, found guilty of war crimes and executed by a firing squad at the precise spot as were the four POWs he had so callously ordered shot back on September 2. At least he died instantly with the merciful swiftness of a volley of accurate rifle fire which is more than could be said for his four unfortunate victims of Japanese barbarism.

The soldiers and civilians of all nations, who had the misfortune to fall into Japanese hands during WW2, suffered so much. Many were murdered, thousands died from sheer neglect. Many who returned home never recovered from their experiences. What the Japanese did to those under their military control was appalling. The bodies of Breavington, Gale, Fletcher and Waters were exhumed by Australian and British burial parties on 22 September 1945. The two Australians now rest in peace in the Kranji War Memorial Cemetery in Singapore.

References.

History of Changi. H. A. Probert. Published by Changi State Prison.1965.

Prisoners of the Japanese. Burgess and Breddon. Time Life 1988.

Northcote Police Station Archives. Melbourne, Victoria. Australia.

Northcote’s Bravest Son. By R. Harcourt. Return Services League Publication 1999.

The Deaths of Breavington, Gale, Waters, Fletcher. By R. Settle

Personal Memories. T. Thwaites Ex RAOC member.

National Archives of Australia-Canberra, ACT,Australia.

[C] KenWright. 2004.