EL ALAMEIN WAR CEMETERY

Alamein

Egypt

Location Information

Alamein is a village, bypassed by the main coast road, approximately 130 kilometres west of Alexandria on the road to Mersa Matruh.

The first Commission road direction sign is located just beyond the Alamein police checkpoint and all visitors should turn off from the main road onto the parallel old coast road.

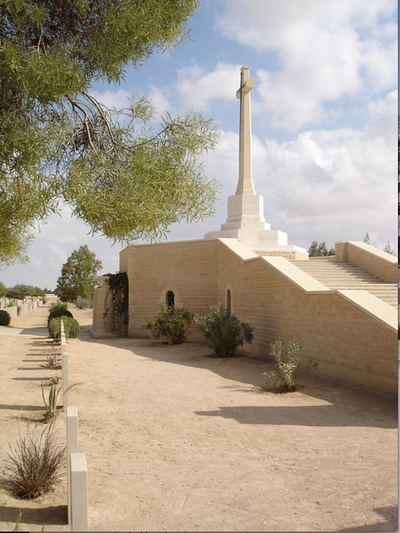

The cemetery lies off the road, slightly beyond a ridge, and is indicated by road direction signs approximately 25 metres before the low metal gates and stone wing walls which are situated centrally at the road edge at the head of the access path into the cemetery. The Cross of Sacrifice feature may be seen from the road.

Visiting Information

Opening times:

The cemetery is open every day from 07:00 - 17:00. Visitors should note that when the gardeners leave the site at 14:30 the visitors book and register book are also removed.

Between 14:30 and 17:00 there is a police guard outside the cemetery. Visitors arriving between these times will be given access, but should bear in mind the absence of the books.

Wheelchair access is signposted.

Historical Information

The campaign in the Western Desert was fought between the Commonwealth forces (with, later, the addition of two brigades of Free French and one each of Polish and Greek troops) all based in Egypt, and the Axis forces (German and Italian) based in Libya. The battlefield, across which the fighting surged back and forth between 1940 and 1942, was the 1,000 kilometres of desert between Alexandria in Egypt and Benghazi in Libya. It was a campaign of manoeuvre and movement, the objectives being the control of the Mediterranean, the link with the east through the Suez Canal, the Middle East oil supplies and the supply route to Russia through Persia.

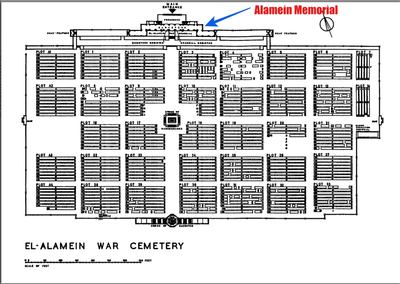

EL ALAMEIN WAR CEMETERY contains the graves of men who died at all stages of the Western Desert campaigns, brought in from a wide area, but especially those who died in the Battle of El Alamein at the end of October 1942 and in the period immediately before that.

The cemetery now contains 7,240 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, of which 815 are unidentified. There are also 102 war graves of other nationalities.

The ALAMEIN CREMATION MEMORIAL, which stands in the south-eastern part of El Alamein War Cemetery, commemorates more than 600 men whose remains were cremated in Egypt and Libya during the war, in accordance with their faith.

The entrance to the cemetery is formed by the ALAMEIN MEMORIAL. The Land Forces panels commemorate more than 8,500 soldiers of the Commonwealth who died in the campaigns in Egypt and Libya, and in the operations of the Eighth Army in Tunisia up to 19 February 1943, who have no known grave. It also commemorates those who served and died in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Persia.

The Air Forces panels commemorate more than 3,000 airmen of the Commonwealth who died in the campaigns in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Greece, Crete and the Aegean, Ethiopia, Eritrea and the Somalilands, the Sudan, East Africa, Aden and Madagascar, who have no known grave. Those who served with the Rhodesian and South African Air Training Scheme and have no known grave are also commemorated here.

The cemetery was designed by Sir J. Hubert Worthington.

Alamein is a village, bypassed by the main coast road, approximately 130 kilometres west of Alexandria on the road to Mersa Matruh.

The first Commission road direction sign is located just beyond the Alamein police checkpoint and all visitors should turn off from the main road onto the parallel old coast road.

The cemetery lies off the road, slightly beyond a ridge, and is indicated by road direction signs approximately 25 metres before the low metal gates and stone wing walls which are situated centrally at the road edge at the head of the access path into the cemetery. The Cross of Sacrifice feature may be seen from the road.

Visiting Information

Opening times:

The cemetery is open every day from 07:00 - 17:00. Visitors should note that when the gardeners leave the site at 14:30 the visitors book and register book are also removed.

Between 14:30 and 17:00 there is a police guard outside the cemetery. Visitors arriving between these times will be given access, but should bear in mind the absence of the books.

Wheelchair access is signposted.

Historical Information

The campaign in the Western Desert was fought between the Commonwealth forces (with, later, the addition of two brigades of Free French and one each of Polish and Greek troops) all based in Egypt, and the Axis forces (German and Italian) based in Libya. The battlefield, across which the fighting surged back and forth between 1940 and 1942, was the 1,000 kilometres of desert between Alexandria in Egypt and Benghazi in Libya. It was a campaign of manoeuvre and movement, the objectives being the control of the Mediterranean, the link with the east through the Suez Canal, the Middle East oil supplies and the supply route to Russia through Persia.

EL ALAMEIN WAR CEMETERY contains the graves of men who died at all stages of the Western Desert campaigns, brought in from a wide area, but especially those who died in the Battle of El Alamein at the end of October 1942 and in the period immediately before that.

The cemetery now contains 7,240 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, of which 815 are unidentified. There are also 102 war graves of other nationalities.

The ALAMEIN CREMATION MEMORIAL, which stands in the south-eastern part of El Alamein War Cemetery, commemorates more than 600 men whose remains were cremated in Egypt and Libya during the war, in accordance with their faith.

The entrance to the cemetery is formed by the ALAMEIN MEMORIAL. The Land Forces panels commemorate more than 8,500 soldiers of the Commonwealth who died in the campaigns in Egypt and Libya, and in the operations of the Eighth Army in Tunisia up to 19 February 1943, who have no known grave. It also commemorates those who served and died in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Persia.

The Air Forces panels commemorate more than 3,000 airmen of the Commonwealth who died in the campaigns in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Greece, Crete and the Aegean, Ethiopia, Eritrea and the Somalilands, the Sudan, East Africa, Aden and Madagascar, who have no known grave. Those who served with the Rhodesian and South African Air Training Scheme and have no known grave are also commemorated here.

The cemetery was designed by Sir J. Hubert Worthington.

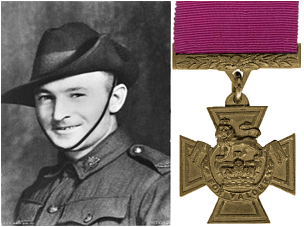

WX10426 Private Percival Eric Gratwick, V. C.

2/48th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F., died between 25th October 1942 and 26th October 1942, aged 40. Plot XXII. A. 6.

Son of Ernest Albert and Eva Mary Gratwick, of Perth, Western Australia.

Citation:

The Citation in the London Gazette of 28th January, 1943, gives the following details: During an attack at Miteiriya Ridge on the night 25th-26th October, 1942, Private Gratwick's platoon was directed at strong enemy positions, but its advance was stopped by intense fire at short range which killed the platoon commander, the platoon serjeant and many others, reducing the platoon strength to seven. Private Gratwick, acting on his own initiative and with utter disregard for his own safety, charged the nearest post and completely destroyed the enemy with hand grenades. He charged a second post, from which the heaviest fire had been directed, and inflicted further casualties, but was killed within striking distance of his objective. By his brave and determined action, Private Gratwick's company was enabled to move forward and mop up its objective. His unselfish courage, his gallant and determined efforts against the heaviest opposition changed a doubtful situation into the successful capture of his company's final objective.

2/48th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F., died between 25th October 1942 and 26th October 1942, aged 40. Plot XXII. A. 6.

Son of Ernest Albert and Eva Mary Gratwick, of Perth, Western Australia.

Citation:

The Citation in the London Gazette of 28th January, 1943, gives the following details: During an attack at Miteiriya Ridge on the night 25th-26th October, 1942, Private Gratwick's platoon was directed at strong enemy positions, but its advance was stopped by intense fire at short range which killed the platoon commander, the platoon serjeant and many others, reducing the platoon strength to seven. Private Gratwick, acting on his own initiative and with utter disregard for his own safety, charged the nearest post and completely destroyed the enemy with hand grenades. He charged a second post, from which the heaviest fire had been directed, and inflicted further casualties, but was killed within striking distance of his objective. By his brave and determined action, Private Gratwick's company was enabled to move forward and mop up its objective. His unselfish courage, his gallant and determined efforts against the heaviest opposition changed a doubtful situation into the successful capture of his company's final objective.

WX9858 Private Arthur Stanley Gurney, V. C.

2/48th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F., died 22nd July 1942, aged 33. Plot XVI. H. 21.

Son of George and Jane Gurney, of Victoria Park, Western Australia.

Citation: The citation in the London Gazette of 8th September, 1942, gives the following details: During an attack on strong German positions at Tell-El-Eisa on 22nd July, 1942, the company to which Private Gurney belonged was held up by intense enemy fire. Heavy casualties were suffered, all the officers being killed or wounded. Private Gurney without hesitation charged and silenced two machine-gun posts. At this stage he was knocked down by a stick grenade, but recovered and charged a third post, using his bayonet with great vigour. His body was found later in an enemy post. By this single-handed act of gallantry in the face of a determined enemy, Private Gurney enabled his company to press forward to its objective. The successful outcome of this engagement was almost entirely due to his heroism at the moment when it was needed.

2/48th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F., died 22nd July 1942, aged 33. Plot XVI. H. 21.

Son of George and Jane Gurney, of Victoria Park, Western Australia.

Citation: The citation in the London Gazette of 8th September, 1942, gives the following details: During an attack on strong German positions at Tell-El-Eisa on 22nd July, 1942, the company to which Private Gurney belonged was held up by intense enemy fire. Heavy casualties were suffered, all the officers being killed or wounded. Private Gurney without hesitation charged and silenced two machine-gun posts. At this stage he was knocked down by a stick grenade, but recovered and charged a third post, using his bayonet with great vigour. His body was found later in an enemy post. By this single-handed act of gallantry in the face of a determined enemy, Private Gurney enabled his company to press forward to its objective. The successful outcome of this engagement was almost entirely due to his heroism at the moment when it was needed.

SX7089 Sergeant William Henry Kibby, V. C.

2/48th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F., died 31st October 1942, aged 39. Plot XVI. A. 18.

Son of John Robert and Mary Isabella Kibby; husband of Sarah Mabel Kibby, of Helmsdale, South Australia

Citation: The citation in the London Gazette of 28th January 1943 gives the following particulars: On 23rd October 1942, during the attack on Meteiriya Ridge, the commander of Serjeant Kibby's platoon was killed, and he assumed command. The platoon had to attack strong enemy positions holding up the advance of their Company. Without thought for his personal safety, Serjeant Kibby dashed forward firing his tommy-gun. This courageous lead resulted in the complete silencing of the enemy fire. On 26th October, under heavy and concentrated enemy artillery attack, Serjeant Kibby not only moved constantly from section to section cheering the men and directing their fire, but several times went out and restored the line of communication. On the night of 30th-31st October, again undeterred by withering enemy fire which mowed down his platoon, Serjeant Kibby pressed on towards the objective. Finally he went forward alone throwing grenades to destroy the last pocket of resistance, then only a few yards away, and was killed. Such outstanding courage, tenacity of purpose and devotion to duty was entirely responsible for the successful capture of the Company's objective. His work was an inspiration to all and he left behind him an example and memory of a soldier who fearlessly and unselfishly fought to the end to carry out his duty.

2/48th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F., died 31st October 1942, aged 39. Plot XVI. A. 18.

Son of John Robert and Mary Isabella Kibby; husband of Sarah Mabel Kibby, of Helmsdale, South Australia

Citation: The citation in the London Gazette of 28th January 1943 gives the following particulars: On 23rd October 1942, during the attack on Meteiriya Ridge, the commander of Serjeant Kibby's platoon was killed, and he assumed command. The platoon had to attack strong enemy positions holding up the advance of their Company. Without thought for his personal safety, Serjeant Kibby dashed forward firing his tommy-gun. This courageous lead resulted in the complete silencing of the enemy fire. On 26th October, under heavy and concentrated enemy artillery attack, Serjeant Kibby not only moved constantly from section to section cheering the men and directing their fire, but several times went out and restored the line of communication. On the night of 30th-31st October, again undeterred by withering enemy fire which mowed down his platoon, Serjeant Kibby pressed on towards the objective. Finally he went forward alone throwing grenades to destroy the last pocket of resistance, then only a few yards away, and was killed. Such outstanding courage, tenacity of purpose and devotion to duty was entirely responsible for the successful capture of the Company's objective. His work was an inspiration to all and he left behind him an example and memory of a soldier who fearlessly and unselfishly fought to the end to carry out his duty.

4270383 Private Adam Herbert Wakenshaw, V. C.

9th Bn. Durham Light Infantry, died 27th June 1942, aged 28. Plot XXXII. D. 9.

Son of Thomas and Mary Wakenshaw, of Newcastle-on-Tyne; husband of Dorothy Ann Wakenshaw, of Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Citation: The London Gazette for 8th September, 1942, gives the following details: On the 27th June, 1942, south of Mersa Matruh, Private Wakenshaw was a member of the crew of a 2-pounder anti-tank gun. An enemy tracked vehicle towing a light gun came within short range. The gun crew opened fire and succeeded in immobilising the enemy vehicle. Another mobile gun came into action, killed or seriously wounded the crew manning the 2-pounder, including Private Wakenshaw, and silenced the 2-pounder. Under intense fire, Private Wakenshaw crawled back to his gun. Although his left arm was blown off, he loaded the gun with one arm and fired five more rounds, setting the tractor on fire and damaging the light gun. A direct hit on the ammunition finally killed him and destroyed the gun. This act of conspicuous gallantry prevented the enemy from using their light gun on the infantry Company which was only 200 yards away. It was through the self sacrifice and courageous devotion to duty of this infantry anti-tank gunner that the Company was enabled to withdraw and to embus in safety.

9th Bn. Durham Light Infantry, died 27th June 1942, aged 28. Plot XXXII. D. 9.

Son of Thomas and Mary Wakenshaw, of Newcastle-on-Tyne; husband of Dorothy Ann Wakenshaw, of Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Citation: The London Gazette for 8th September, 1942, gives the following details: On the 27th June, 1942, south of Mersa Matruh, Private Wakenshaw was a member of the crew of a 2-pounder anti-tank gun. An enemy tracked vehicle towing a light gun came within short range. The gun crew opened fire and succeeded in immobilising the enemy vehicle. Another mobile gun came into action, killed or seriously wounded the crew manning the 2-pounder, including Private Wakenshaw, and silenced the 2-pounder. Under intense fire, Private Wakenshaw crawled back to his gun. Although his left arm was blown off, he loaded the gun with one arm and fired five more rounds, setting the tractor on fire and damaging the light gun. A direct hit on the ammunition finally killed him and destroyed the gun. This act of conspicuous gallantry prevented the enemy from using their light gun on the infantry Company which was only 200 yards away. It was through the self sacrifice and courageous devotion to duty of this infantry anti-tank gunner that the Company was enabled to withdraw and to embus in safety.

WX3667 Bombardier

William John De Ranulph Edwards

A.I.F. 2/7 Fd. Regt., Royal Australian Artillery

26th August 1942, aged 39.

Plot A II. E. 20.

Son of Horace James Gomez Edwards and Rose Amelia Edwards; husband of Irene Doris Edwards, of Balwyn, Victoria, Australia.

William John De Ranulph Edwards

A.I.F. 2/7 Fd. Regt., Royal Australian Artillery

26th August 1942, aged 39.

Plot A II. E. 20.

Son of Horace James Gomez Edwards and Rose Amelia Edwards; husband of Irene Doris Edwards, of Balwyn, Victoria, Australia.

VX3383 Corporal

Edward James Graham

A.I.F. 2/24 Bn. Australian Infantry

24th October 1942, aged 36.

Plot XXII. C. 14.

Son of James Henry Graham and Annie Graham, of Devonport, New Zealand.

Lived at 32 Church Street, Devonport, Auckland, New Zealand

Remembered by his Grandson Steve Graham

Edward James Graham

A.I.F. 2/24 Bn. Australian Infantry

24th October 1942, aged 36.

Plot XXII. C. 14.

Son of James Henry Graham and Annie Graham, of Devonport, New Zealand.

Lived at 32 Church Street, Devonport, Auckland, New Zealand

Remembered by his Grandson Steve Graham

To Make One Weep

Text and pictures provided by Ken Wright

QX3026 Sergeant

Herbert Thomas Leeson, D. C. M.

2/32 Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

31st October 1942, aged 24.

Plot AIII. B. 26.

Son of Thomas Alfred and Emma Leeson; husband of Sylvia Mary Leeson, of South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

In the Commonwealth El Alamein War Cemetery in Egypt, there are the graves of men who died at all stages of the Western Desert campaigns brought in from a wide area, but especially those who died in the Battle of El Alamein at the end of October 1942 and the period immediately before that. The cemetery now contains 7,240 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War of which 815 are unidentified. There are also 102 war graves of other nationalities.Behind every headstone in the cemetery there is a story. A tale of shattered hopes and dreams. A life cut violently short. Someone's son, brother, lover or husband. Killed in a war trying to kill someone else's brother, son or husband. Both sides doing a dirty job that the politicians and generals said had to be done. One such grave belongs to Sergeant Herbert Thomas 'Curly' Leeson. He was 21 years old married electricians labourer when he enlisted in the 9th Division, 13 Platoon, 2/32 Australian Infantry Forces. He left his Australian state of Queensland bound for the Middle East on 4th May 1940. His service records he had leadership qualities but his devil may care attitude had him going to Lance Corporal to Private then back up to Lance Corporal to Corporal to Acting Sergeant and then back to Corporal. It was in the Egyptian desert that fate dealt him its final hand. I was also where he and so many of his countrymen showed the world what they could do on the battlefield.

The Campaign in the Western Desert of North Africa was a fight between the Commonwealth forces [with a later addition of two Brigades of Free French and one each of Polish and Greek troops] all based in Egypt and the Axis forces [German and Italian] based in Libya. The battle field across which the fighting surged back and forth between 1940 and 1942 was 1,000 kilometres of desert between Alexandria in Egypt and Benghazi in Libya. It was a campaign of manoeuvre and movement, the object being the control of the Mediterranean, the link with the east through the Suez Canal, the Middle East oil supplies, the supply route to Russia through Persia [Iran] and the vital links to India, Australia and the Indian Ocean. El Alamein was to become one of the most decisive battles of WW2 both strategically and psychologically and initiated the decline of the Axis power in the Mediterranean.

On 13 September, 1940, the Italian dictator Mussolini began the war in North Africa when five Italian divisions launched an attack into Egypt. The Italian forces halted at Sidi Barrani and consolidated. The British forces retreated to Mersa Matruh. On December 9, Commonwealth forces struck back and by mid December, the Italian army had been forced out of Egypt and was fighting a defensive war. Hitler sent General Erwin Rommel with his Panzer Afrika Korps and elements of the Luftwaffe to bolster Mussolini’s army in March 1941. His instructions were to take command of the combined Italian/German preparations against the British and Commonwealth Forces and eventually seize the Suez Canal.

Over the next ten months, a series of battles took place with the fortunes of war shifting back and forth between the two opposing armies. El Agheila, Tobruk, Sidi-Rezegh, Bardia and Halfaya to name a few. Troops on both sides were doing their best to do their duty and stay alive in the sweltering heat of the day, the freezing cold of the desert at night, the constant irritation of flies and sand and the ever present threat of death or mutilation.

By 1941, during the siege of Tobruk 'Curly' Leeson had settled into the role of rank and responsibility. Records show Corporal Leeson and his six man patrol from the 2/32 Battalion on the 24/25th July stalked to German crews manning a machine gun and a mortar. The Germans were moving their weapons from point to point in a truck to counter-attack another patrol of the 2/32 which had become embroiled in a fire fight with enemy unexpectedly encountered in foxholes close to the Australian’s wire. Many, more than once risked death or injury on night patrols but by stealth, quick action and luck, outwitted and killed their opponents. The Australians had a grim reputation among the troops of the Afrika Corps for their terrible work with the bayonet so clashes were sometimes silent but bloody affairs.

By January 1942, the war had swung in favour of the Axis forces and by the end of June, Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika had pushed the Allies back deep into Egypt and the capture of Cairo and the Suez Canal seemed a distinct possibility. In desperation, the Allies established a new defensive position approximately 30 miles wide near the tiny railway station of El Alamein and hoped the impassable Qattara Depression [133 metres below sea level and containing at its lowest point a large salt pan] on one side and the Egyptian coast on the other would narrow the battlefield enough for them to make a stand and it was here that the fate of the whole campaign would be decided. The combined German/Italian force amounted to 180,000 men, 600 tanks and 500 guns. Opposing the Axis forces, were the Eighth Army commanded by General Claude Auchinleck with about 220,000 men, 1,100 tanks and 900 artillery pieces. This army was comprised of British, New Zealand, South African, Indian and the Australian Ninth Division under General Leslie Morshead. The Australians were to play a crucial role in two of the three important and decisive battles around El Alamein which helped to ensure the Allied victory in North Africa.

The first major battle of El Alamein from the Australian perspective comes from the war diaries and unit history of the 2/32 Australian Infantry Battalion.

16th July, 1942. 2230 hours. After a final conference the 2/32 Battalion comprising four companies moved forward quietly on foot towards the start line at midnight.

17 July, 0230 hours. The Battalion moved forward ready to attack the enemy position. A-Company to the right, B-Company to the centre, C-Company to the left with D-Company held in reserve. The position to be taken was a ridge of high ground commencing from Trig point 22 in the north which was A-Company’s objective to the Qattara track in the south which was C-Company’s task. A silent advance brought the Australians very close to the enemy position. The Battalion quickly mopped up enemy posts and commenced consolidating the objectives. Approximately 700 Italian prisoners were taken and the battalion only suffered light casualties. D-Company although not actively involved in the attack was ordered forward and took up a new position between Trig 22 and B-Company. Due to radio failure, contact with A-Company had been lost earlier that morning and it was later established that for some reason, they had exploited too far and overshot their mark in the darkness by about1,500 yards.

From the Battalion History, Sergeant Jack Calder, A-Company summed up the situation in a report after the war. ‘At daylight it could be seen the company was in a perilous position with enemy armoured vehicles of various types placed on three sides of the company which was well forward of the other companies. The men were not dug in as the area we occupied as a defensive position was mainly rock. This was used to the best advantage by the men who built small mounds of rocks to shelter behind. When light tanks and armoured vehicles began to attack the position shortly after 7 am, they had completely surrounded us. A German officer called out to us to lay down our arms and surrender. Captain Forwood, the officer in charge realised we were in a hopeless position and had no other option but to surrender. The whole company, 3 officers and 98 men became prisoners of war.

B-Company had captured its objective and took 60 prisoners and C-Company had also been successful as well as capturing 50 Italians and a number of 20 mm Breda guns. The Breda began service in the Italian Army in 1935 and was designed as a three crew duel purpose weapon for use against ground and air targets. Corporal Leeson, a qualified weapons instructor from 13 Platoon, C- Company, soon had one of these weapons working. . It took a long time before the Axis forces realised an attack was taking place but as daylight came, the enemy bombarded the Australian forward positions with mortars, machine gun and regular artillery fire including the use of the dreaded 88mm gun airburst shells. It was impossible to dig effective weapon pits or foxholes on the Makh Khad Ridge as the feature was called as it was just about solid rock and stones. The enemy brought up tanks and armoured cars which, owing to the inability of our anti tank guns to secure suitable positions were able to shoot up our troops with impunity. Casualties began to mount all along the newly acquired positions. A particularly good effort to prevent this was made by Corporal Leeson.

During the first two enemy counter attacks, Corporal Leeson manned a captured Breda and under heavy fire, destroyed three enemy armoured cars before a direct hit from an anti tank shell knocked him out of the weapons pit and damaged the gun. Although wounded, he managed to repair the weapon and continued to engage the enemy. Later, under heavy machine gun and artillery fire he went to the assistance of a wounded man just forward from his position and carried him to safety. He was wounded again, this time more seriously but returned to the gun and continue to engage the enemy armour and low flying aircraft.

About 5pm enemy tanks made a strong attack against the junction of C-Company and the 2/43 Battalion. Two of the platoons of C-Company were over-run and 22 men captured. In spite of this, the defence held firm, ably assisted by the gunnery of Lance-Sergeant D.A.Daley of the 2/3 Anti Tank Regiment who knocked out 6 tanks. It had been a costly day. Apart from the loss of A-Company, B-Company had suffered 12 men killed in action and 26 wounded, including the company commander, Captain R.Joshua and Lieutenant H.C.Trotter. Two were taken prisoner. C-Company lost 3 men killed and 19 wounded including the company commander, Captain P.R.Jacoby and Lieutenant R.G.Cronk. Twenty three men taken prisoner. Five men in D-Company had been killed and 14 wounded including Lieutenant B.G.Green. Sixteen men had been taken prisoner, Headquarter Company and Battalion Headquarters, both in the thick of battle also had their share of casualties with HQ Company losing 4 killed and 13 wounded while Battalion HQ had 4 taken prisoner and 1 wounded.

The Australian action in the El Alamein sector hardly gives the impression that it was a resounding success and the troops themselves probably felt little had been achieved for such a great cost. However, when the bigger picture is considered, it was the aggressive tactics of 24 and 26 Brigades which forced the enemy to bring reinforcements up from the central sector and so abandon plans for an attack in that area. To quote from the official history, Barton Maugham’s Tobruk and El Alamein.

‘The 24th Brigade had taken 736 prisoners who included men from both infantry regiments of the Trento Division, from one regiment of the Trieste and one from the 7th Bersaglieri Regiment [Corps troops]. It had achieved more that day than the local tactical importance of the ground taken would signify. The operation had far reaching effects’.

A certain amount of praise should be gained from Field Marshall Rommel, the ‘Desert Fox’ himself when he wrote to his wife on July 17; ‘It is going pretty badly for me. The enemy is using his superiority especially in infantry to destroy the Italian formations one by one and the German formations are much too weak to stand alone. It’s enough to make one weep.’

Corporal Leeson along with the other wounded was transferred to hospital for medical treatment. It was during his convalescence that he was promoted to Acting Sergeant and on 12th September, Sergeant Herbert Thomas Leeson was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions in the battle of 17th July. By mid October he was back to active service on special duties at HQ possibly in the role as weapons instructor to HQ staff. He rejoined his old unit on the 27th. Although General Auchinleck was successful in weakening the Axis forces, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill replaced him with General Alexander on August 8th. Alexander took up the position of Commander of all the British forces in the Middle East with General Bernard Montgomery in command of the 8th army.

On the night of October 30, the 2/32 Battalion began an attack at 10pm towards the railway line. Despite mounting casualties, they captured the vital one kilometre objective known as the ‘Saucer’ This area included a German medical post, the blockhouse, Barrel hill and a crossing in the railway embankment. During the following day, the Australians struggled to hold the area but together with British troops, they fought a furious battle against a German counter attack with tanks. They still held the position by the evening of November 1.

While the Australians absorbed Rommels attention, Montgomery launched ‘’Operation Supercharge’’ at 1-05 on November 2. It was a planned tank breakthrough to the south at Rommel’s weakest point. After fierce fighting the enemy line was broken near Tel El Aggagir by November 4 and the Axis forces were forced to retreat back towards the Libyan border. Rommel had wirelessed his decision and reasons for the retreat to Hitler. While the retreat was in progress a message arrived from Hitler’s HQ. ‘‘The situation demands that the positions at El Alamein be held to the last man. A retreat is out of the question. Victory or Death! Heil Hitler!’’ Rommel acknowledged the signal but chose to ignore it. Hitler’s incredibly stupid order to stand and fight to the last man would have meant the complete destruction of his army and Rommel knew, as any good tactician should, his first priority was to save what was left of his army by retreating and regrouping to fight again. Although the battle for El Alamein was over, the Axis forces continued to fight a losing battle. By 12 May, 1943, all German and Italian forces in North Africa surrendered. Approximately 275,000 Axis prisoners were taken. Six hundred and sixty three escaped.

In the war there are no winners or losers, only dead heroes and grieving widows. The butcher's bill for the men of the Eighth Army killed, wounded or missing was over 13,500. Of these 2,694 were Australians of the 9th Division and roughly one-fifth of the total army's total casualties. Australian dead numbered 620. It was the last major battle fought by Australian ground forces in the Middle East as the 9th Division were recalled back to Australia and eventually re-assigned to fight the Japanese in the pacific.

Sergeant Herbert Thomas Leeson D.C.M., did not return home to Australia with his mates or see his wife or parents. He was killed in action on October 31st near the El Alamein railway station. His grave stone in the El Alamein War Cemetery is a stark reminder of how many of the 9th Division paid the ultimate sacrifice. The survivors walked tall and proud after the war was over and they never have forgotten the comrades they left behind.

Footnote. [1]

The Commonwealth War Cemetery at El Alamein was inaugurated in 1954 and five years later, a 33 metre high octagonal mausoleum dedicated to the 4,634 Italian dead was opened on January 9 just a few kilometres west of the Commonwealth Cemetery. That same year, on a ridge between the Italian and Commonwealth cemeteries, a memorial to the German dead was opened on October 19. Within this fortress like mausoleum are the names of approximately 4,200 Deutsche Soldaten.

Footnote. [2]

Award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal QX3026 Corporal Herbert Thomas Leeson, [El Alamein Battle.]

Corporal Herbert Thomas Leeson was a member of 13 Platoon C Company and took part in the attack in the vicinity of Tel el Eisa on 17 July 1942. After consolidation he asked to be allowed to use a captured 20mm Breda. During the two enemy counter attacks, under heavy machine- gun, anti tank and mortar fire, he single handed destroyed two and probably three enemy vehicles before the gun was put out of action by a direct hit from an anti tank shell, which knocked Corporal Leeson out of the pit and wounded him in the face. However, despite the injury, he immediately repaired the gun and continued to engage the enemy.

Later, on hearing of a wounded man lying exposed to fire in front of the right flank, with complete disregard for his own safety and in the face of heavy machine- gun fire, Corporal Leeson left the pit and went to the assistance of this man and carried him to safety. In this act, Corporal Leeson sustained a more serious wound to his hip, but disregarding his injuries, he immediately returned to his gun and commenced fire at low flying aircraft. The initiative, courage and devotion to duty displayed by Corporal Leeson throughout were an inspiration to his men.

References

H.T.Leeson. Service Records. National Archives of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

War Diary. 2/32 Australian Infantry Battalion. July 1942. National Archives, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission. [permission to use material from web site]

Britain to Borneo. A History of the 2/32 Australian Infantry Battalion. S.Trigellis Smith. Private Publication. 1993. [with special thanks to John Grant and Jack Calder

Australians in the War 1939-45 [ Army] Tobruk and El Alamein. Barton Maughan. 1966. Australian War Memorial, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Rommel Papers. [Letter Quote] edited by B.H.Liddell-Hart. Collins, London.1953. [page 257]

Jack Calder. Wagga Wagga. New South Wales. Australia.

John Grant. Croydon Park, New South Wales. Australia.

Jack Castle. Doncaster, Victoria, Australia.

Australian War Memorial. Canberra, ACT, Australia. For permission to use material from their Encyclopedia [El Alamein] web site.

Hitlers Telegram. With Rommel in the Desert. Heinz.W.Schmidt, Harrop London, 1980. [page 177]

Photographs. Authors collection.

© Ken Wright. 2005.

Herbert Thomas Leeson, D. C. M.

2/32 Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

31st October 1942, aged 24.

Plot AIII. B. 26.

Son of Thomas Alfred and Emma Leeson; husband of Sylvia Mary Leeson, of South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

In the Commonwealth El Alamein War Cemetery in Egypt, there are the graves of men who died at all stages of the Western Desert campaigns brought in from a wide area, but especially those who died in the Battle of El Alamein at the end of October 1942 and the period immediately before that. The cemetery now contains 7,240 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War of which 815 are unidentified. There are also 102 war graves of other nationalities.Behind every headstone in the cemetery there is a story. A tale of shattered hopes and dreams. A life cut violently short. Someone's son, brother, lover or husband. Killed in a war trying to kill someone else's brother, son or husband. Both sides doing a dirty job that the politicians and generals said had to be done. One such grave belongs to Sergeant Herbert Thomas 'Curly' Leeson. He was 21 years old married electricians labourer when he enlisted in the 9th Division, 13 Platoon, 2/32 Australian Infantry Forces. He left his Australian state of Queensland bound for the Middle East on 4th May 1940. His service records he had leadership qualities but his devil may care attitude had him going to Lance Corporal to Private then back up to Lance Corporal to Corporal to Acting Sergeant and then back to Corporal. It was in the Egyptian desert that fate dealt him its final hand. I was also where he and so many of his countrymen showed the world what they could do on the battlefield.

The Campaign in the Western Desert of North Africa was a fight between the Commonwealth forces [with a later addition of two Brigades of Free French and one each of Polish and Greek troops] all based in Egypt and the Axis forces [German and Italian] based in Libya. The battle field across which the fighting surged back and forth between 1940 and 1942 was 1,000 kilometres of desert between Alexandria in Egypt and Benghazi in Libya. It was a campaign of manoeuvre and movement, the object being the control of the Mediterranean, the link with the east through the Suez Canal, the Middle East oil supplies, the supply route to Russia through Persia [Iran] and the vital links to India, Australia and the Indian Ocean. El Alamein was to become one of the most decisive battles of WW2 both strategically and psychologically and initiated the decline of the Axis power in the Mediterranean.

On 13 September, 1940, the Italian dictator Mussolini began the war in North Africa when five Italian divisions launched an attack into Egypt. The Italian forces halted at Sidi Barrani and consolidated. The British forces retreated to Mersa Matruh. On December 9, Commonwealth forces struck back and by mid December, the Italian army had been forced out of Egypt and was fighting a defensive war. Hitler sent General Erwin Rommel with his Panzer Afrika Korps and elements of the Luftwaffe to bolster Mussolini’s army in March 1941. His instructions were to take command of the combined Italian/German preparations against the British and Commonwealth Forces and eventually seize the Suez Canal.

Over the next ten months, a series of battles took place with the fortunes of war shifting back and forth between the two opposing armies. El Agheila, Tobruk, Sidi-Rezegh, Bardia and Halfaya to name a few. Troops on both sides were doing their best to do their duty and stay alive in the sweltering heat of the day, the freezing cold of the desert at night, the constant irritation of flies and sand and the ever present threat of death or mutilation.

By 1941, during the siege of Tobruk 'Curly' Leeson had settled into the role of rank and responsibility. Records show Corporal Leeson and his six man patrol from the 2/32 Battalion on the 24/25th July stalked to German crews manning a machine gun and a mortar. The Germans were moving their weapons from point to point in a truck to counter-attack another patrol of the 2/32 which had become embroiled in a fire fight with enemy unexpectedly encountered in foxholes close to the Australian’s wire. Many, more than once risked death or injury on night patrols but by stealth, quick action and luck, outwitted and killed their opponents. The Australians had a grim reputation among the troops of the Afrika Corps for their terrible work with the bayonet so clashes were sometimes silent but bloody affairs.

By January 1942, the war had swung in favour of the Axis forces and by the end of June, Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika had pushed the Allies back deep into Egypt and the capture of Cairo and the Suez Canal seemed a distinct possibility. In desperation, the Allies established a new defensive position approximately 30 miles wide near the tiny railway station of El Alamein and hoped the impassable Qattara Depression [133 metres below sea level and containing at its lowest point a large salt pan] on one side and the Egyptian coast on the other would narrow the battlefield enough for them to make a stand and it was here that the fate of the whole campaign would be decided. The combined German/Italian force amounted to 180,000 men, 600 tanks and 500 guns. Opposing the Axis forces, were the Eighth Army commanded by General Claude Auchinleck with about 220,000 men, 1,100 tanks and 900 artillery pieces. This army was comprised of British, New Zealand, South African, Indian and the Australian Ninth Division under General Leslie Morshead. The Australians were to play a crucial role in two of the three important and decisive battles around El Alamein which helped to ensure the Allied victory in North Africa.

The first major battle of El Alamein from the Australian perspective comes from the war diaries and unit history of the 2/32 Australian Infantry Battalion.

16th July, 1942. 2230 hours. After a final conference the 2/32 Battalion comprising four companies moved forward quietly on foot towards the start line at midnight.

17 July, 0230 hours. The Battalion moved forward ready to attack the enemy position. A-Company to the right, B-Company to the centre, C-Company to the left with D-Company held in reserve. The position to be taken was a ridge of high ground commencing from Trig point 22 in the north which was A-Company’s objective to the Qattara track in the south which was C-Company’s task. A silent advance brought the Australians very close to the enemy position. The Battalion quickly mopped up enemy posts and commenced consolidating the objectives. Approximately 700 Italian prisoners were taken and the battalion only suffered light casualties. D-Company although not actively involved in the attack was ordered forward and took up a new position between Trig 22 and B-Company. Due to radio failure, contact with A-Company had been lost earlier that morning and it was later established that for some reason, they had exploited too far and overshot their mark in the darkness by about1,500 yards.

From the Battalion History, Sergeant Jack Calder, A-Company summed up the situation in a report after the war. ‘At daylight it could be seen the company was in a perilous position with enemy armoured vehicles of various types placed on three sides of the company which was well forward of the other companies. The men were not dug in as the area we occupied as a defensive position was mainly rock. This was used to the best advantage by the men who built small mounds of rocks to shelter behind. When light tanks and armoured vehicles began to attack the position shortly after 7 am, they had completely surrounded us. A German officer called out to us to lay down our arms and surrender. Captain Forwood, the officer in charge realised we were in a hopeless position and had no other option but to surrender. The whole company, 3 officers and 98 men became prisoners of war.

B-Company had captured its objective and took 60 prisoners and C-Company had also been successful as well as capturing 50 Italians and a number of 20 mm Breda guns. The Breda began service in the Italian Army in 1935 and was designed as a three crew duel purpose weapon for use against ground and air targets. Corporal Leeson, a qualified weapons instructor from 13 Platoon, C- Company, soon had one of these weapons working. . It took a long time before the Axis forces realised an attack was taking place but as daylight came, the enemy bombarded the Australian forward positions with mortars, machine gun and regular artillery fire including the use of the dreaded 88mm gun airburst shells. It was impossible to dig effective weapon pits or foxholes on the Makh Khad Ridge as the feature was called as it was just about solid rock and stones. The enemy brought up tanks and armoured cars which, owing to the inability of our anti tank guns to secure suitable positions were able to shoot up our troops with impunity. Casualties began to mount all along the newly acquired positions. A particularly good effort to prevent this was made by Corporal Leeson.

During the first two enemy counter attacks, Corporal Leeson manned a captured Breda and under heavy fire, destroyed three enemy armoured cars before a direct hit from an anti tank shell knocked him out of the weapons pit and damaged the gun. Although wounded, he managed to repair the weapon and continued to engage the enemy. Later, under heavy machine gun and artillery fire he went to the assistance of a wounded man just forward from his position and carried him to safety. He was wounded again, this time more seriously but returned to the gun and continue to engage the enemy armour and low flying aircraft.

About 5pm enemy tanks made a strong attack against the junction of C-Company and the 2/43 Battalion. Two of the platoons of C-Company were over-run and 22 men captured. In spite of this, the defence held firm, ably assisted by the gunnery of Lance-Sergeant D.A.Daley of the 2/3 Anti Tank Regiment who knocked out 6 tanks. It had been a costly day. Apart from the loss of A-Company, B-Company had suffered 12 men killed in action and 26 wounded, including the company commander, Captain R.Joshua and Lieutenant H.C.Trotter. Two were taken prisoner. C-Company lost 3 men killed and 19 wounded including the company commander, Captain P.R.Jacoby and Lieutenant R.G.Cronk. Twenty three men taken prisoner. Five men in D-Company had been killed and 14 wounded including Lieutenant B.G.Green. Sixteen men had been taken prisoner, Headquarter Company and Battalion Headquarters, both in the thick of battle also had their share of casualties with HQ Company losing 4 killed and 13 wounded while Battalion HQ had 4 taken prisoner and 1 wounded.

The Australian action in the El Alamein sector hardly gives the impression that it was a resounding success and the troops themselves probably felt little had been achieved for such a great cost. However, when the bigger picture is considered, it was the aggressive tactics of 24 and 26 Brigades which forced the enemy to bring reinforcements up from the central sector and so abandon plans for an attack in that area. To quote from the official history, Barton Maugham’s Tobruk and El Alamein.

‘The 24th Brigade had taken 736 prisoners who included men from both infantry regiments of the Trento Division, from one regiment of the Trieste and one from the 7th Bersaglieri Regiment [Corps troops]. It had achieved more that day than the local tactical importance of the ground taken would signify. The operation had far reaching effects’.

A certain amount of praise should be gained from Field Marshall Rommel, the ‘Desert Fox’ himself when he wrote to his wife on July 17; ‘It is going pretty badly for me. The enemy is using his superiority especially in infantry to destroy the Italian formations one by one and the German formations are much too weak to stand alone. It’s enough to make one weep.’

Corporal Leeson along with the other wounded was transferred to hospital for medical treatment. It was during his convalescence that he was promoted to Acting Sergeant and on 12th September, Sergeant Herbert Thomas Leeson was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions in the battle of 17th July. By mid October he was back to active service on special duties at HQ possibly in the role as weapons instructor to HQ staff. He rejoined his old unit on the 27th. Although General Auchinleck was successful in weakening the Axis forces, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill replaced him with General Alexander on August 8th. Alexander took up the position of Commander of all the British forces in the Middle East with General Bernard Montgomery in command of the 8th army.

On the night of October 30, the 2/32 Battalion began an attack at 10pm towards the railway line. Despite mounting casualties, they captured the vital one kilometre objective known as the ‘Saucer’ This area included a German medical post, the blockhouse, Barrel hill and a crossing in the railway embankment. During the following day, the Australians struggled to hold the area but together with British troops, they fought a furious battle against a German counter attack with tanks. They still held the position by the evening of November 1.

While the Australians absorbed Rommels attention, Montgomery launched ‘’Operation Supercharge’’ at 1-05 on November 2. It was a planned tank breakthrough to the south at Rommel’s weakest point. After fierce fighting the enemy line was broken near Tel El Aggagir by November 4 and the Axis forces were forced to retreat back towards the Libyan border. Rommel had wirelessed his decision and reasons for the retreat to Hitler. While the retreat was in progress a message arrived from Hitler’s HQ. ‘‘The situation demands that the positions at El Alamein be held to the last man. A retreat is out of the question. Victory or Death! Heil Hitler!’’ Rommel acknowledged the signal but chose to ignore it. Hitler’s incredibly stupid order to stand and fight to the last man would have meant the complete destruction of his army and Rommel knew, as any good tactician should, his first priority was to save what was left of his army by retreating and regrouping to fight again. Although the battle for El Alamein was over, the Axis forces continued to fight a losing battle. By 12 May, 1943, all German and Italian forces in North Africa surrendered. Approximately 275,000 Axis prisoners were taken. Six hundred and sixty three escaped.

In the war there are no winners or losers, only dead heroes and grieving widows. The butcher's bill for the men of the Eighth Army killed, wounded or missing was over 13,500. Of these 2,694 were Australians of the 9th Division and roughly one-fifth of the total army's total casualties. Australian dead numbered 620. It was the last major battle fought by Australian ground forces in the Middle East as the 9th Division were recalled back to Australia and eventually re-assigned to fight the Japanese in the pacific.

Sergeant Herbert Thomas Leeson D.C.M., did not return home to Australia with his mates or see his wife or parents. He was killed in action on October 31st near the El Alamein railway station. His grave stone in the El Alamein War Cemetery is a stark reminder of how many of the 9th Division paid the ultimate sacrifice. The survivors walked tall and proud after the war was over and they never have forgotten the comrades they left behind.

Footnote. [1]

The Commonwealth War Cemetery at El Alamein was inaugurated in 1954 and five years later, a 33 metre high octagonal mausoleum dedicated to the 4,634 Italian dead was opened on January 9 just a few kilometres west of the Commonwealth Cemetery. That same year, on a ridge between the Italian and Commonwealth cemeteries, a memorial to the German dead was opened on October 19. Within this fortress like mausoleum are the names of approximately 4,200 Deutsche Soldaten.

Footnote. [2]

Award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal QX3026 Corporal Herbert Thomas Leeson, [El Alamein Battle.]

Corporal Herbert Thomas Leeson was a member of 13 Platoon C Company and took part in the attack in the vicinity of Tel el Eisa on 17 July 1942. After consolidation he asked to be allowed to use a captured 20mm Breda. During the two enemy counter attacks, under heavy machine- gun, anti tank and mortar fire, he single handed destroyed two and probably three enemy vehicles before the gun was put out of action by a direct hit from an anti tank shell, which knocked Corporal Leeson out of the pit and wounded him in the face. However, despite the injury, he immediately repaired the gun and continued to engage the enemy.

Later, on hearing of a wounded man lying exposed to fire in front of the right flank, with complete disregard for his own safety and in the face of heavy machine- gun fire, Corporal Leeson left the pit and went to the assistance of this man and carried him to safety. In this act, Corporal Leeson sustained a more serious wound to his hip, but disregarding his injuries, he immediately returned to his gun and commenced fire at low flying aircraft. The initiative, courage and devotion to duty displayed by Corporal Leeson throughout were an inspiration to his men.

References

H.T.Leeson. Service Records. National Archives of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

War Diary. 2/32 Australian Infantry Battalion. July 1942. National Archives, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission. [permission to use material from web site]

Britain to Borneo. A History of the 2/32 Australian Infantry Battalion. S.Trigellis Smith. Private Publication. 1993. [with special thanks to John Grant and Jack Calder

Australians in the War 1939-45 [ Army] Tobruk and El Alamein. Barton Maughan. 1966. Australian War Memorial, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Rommel Papers. [Letter Quote] edited by B.H.Liddell-Hart. Collins, London.1953. [page 257]

Jack Calder. Wagga Wagga. New South Wales. Australia.

John Grant. Croydon Park, New South Wales. Australia.

Jack Castle. Doncaster, Victoria, Australia.

Australian War Memorial. Canberra, ACT, Australia. For permission to use material from their Encyclopedia [El Alamein] web site.

Hitlers Telegram. With Rommel in the Desert. Heinz.W.Schmidt, Harrop London, 1980. [page 177]

Photographs. Authors collection.

© Ken Wright. 2005.